Nigeria’s cities are at severe risk from climate change. Time to build resilience, and fast

By Abiola Durodola, an Urban Planner and Team Lead of AdvoKC Foundation, with additional reporting from Abiade Idunnu, a Flood Risk Analyst | November 10, 2022

Nigeria’s population is on the increase. By 2030, more than 60% of the country’s population will be living in cities. As the country’s population continues to grow, so does its environmental crisis across mutiple ecological zones.

In the Northern part, the wind erosion that has swept away houses and farms has intensified the effects of deforestation, drought, over-grazing, and desertification. In many of the towns along the Sahelian zones, the climate crisis is unleashing increasing desertification. In addition, states along the country’s coastal region are also in the ‘dip’. The consistent waves, flooding, and climate change-induced sea level rises have led millions of people to ‘count their loss’. In the middle belt region of Nigeria, gully erosion and flooding are forcing people to leave their ancestral homes to settle in internally-displaced people camps that scatter across the region.

In the Southern region, flash and seasonal flooding caused by climate change are ruining cities. In August 2011, Ibadan, one of Nigeria’s populous cities, witnessed historic flooding caused by an all-time high of 187.5mm rainfall and indiscriminate dumping of solid wastes on water channels. This eventually left over one thousand people dead and destroyed properties worth millions of naira. Before this historic flooding, the city had already witnessed varying degrees of flooding in areas along the Ogunpa and Kudeti streams in the city in 1955, 1960, 1961, 1963, 1978 1980, with the most recent in 2011. Since then, the state has continued to witness flash floods caused by environmental degradation and heavy rains.

Every year, rising sea levels in Lagos, Nigeria’s commercial city capital, almost always lead to seasonal flooding in the Lekki, Ikoyi, Epe, and some parts of the Mainland areas in the state. Its impacts on the country’s most populous city are far-reaching, as business owners and residents count their loss, the major roads are not also left unaffected as they are worn in many places, and the poorly-constructed asphalt on the road are stripped to the red earth beneath, while residents seek refuge in designated camps. In 2021, Jigawa, Bauchi and Adamawa states in the North-East region of Nigeria were also inundated by flood which evicted over 380 households and left more than 20 people dead.

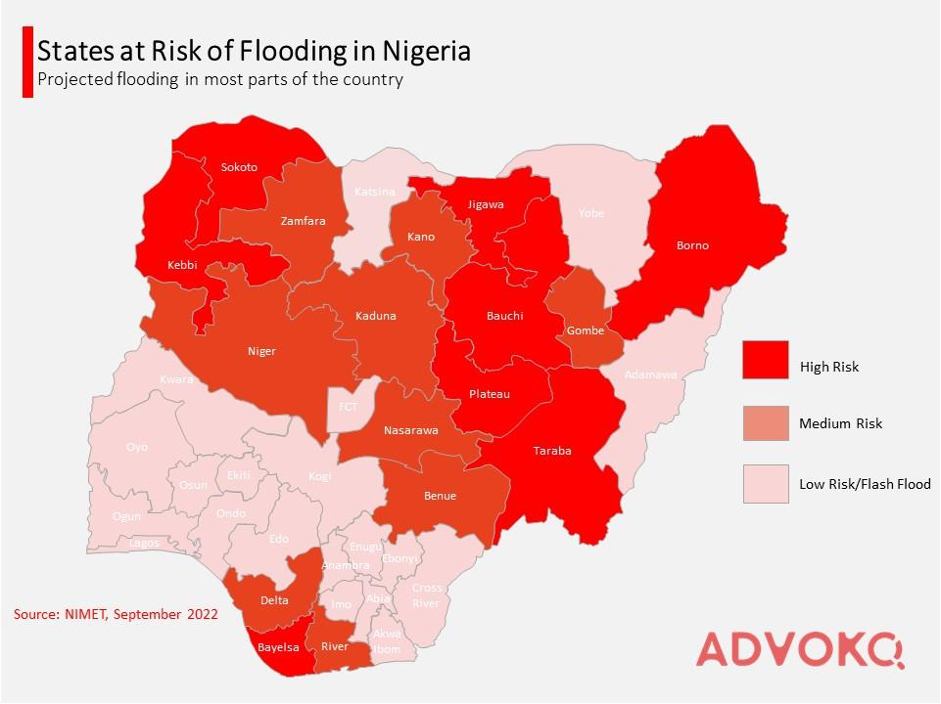

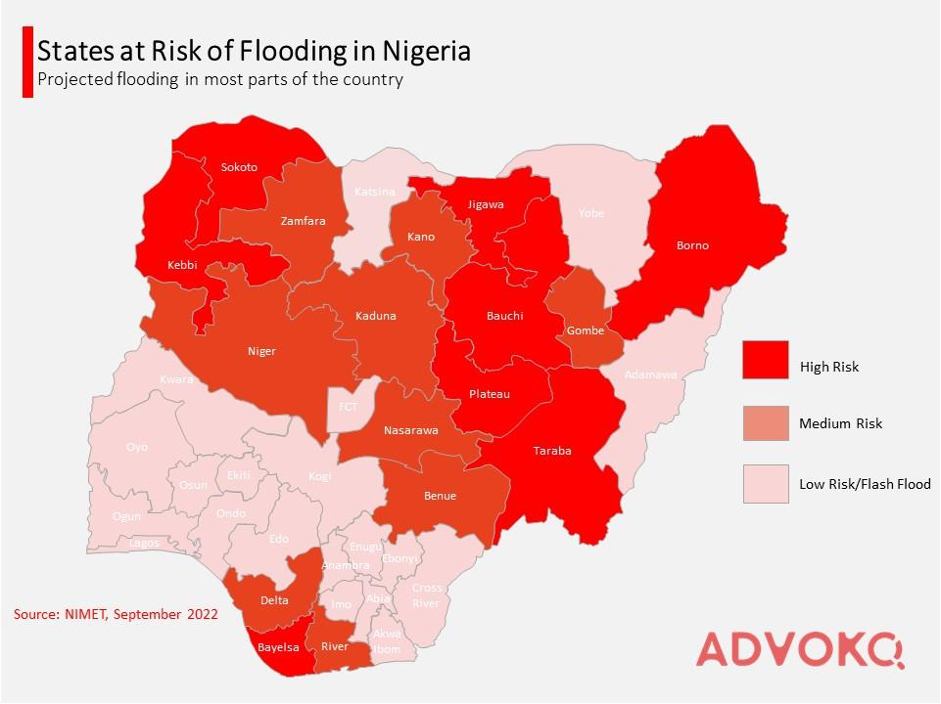

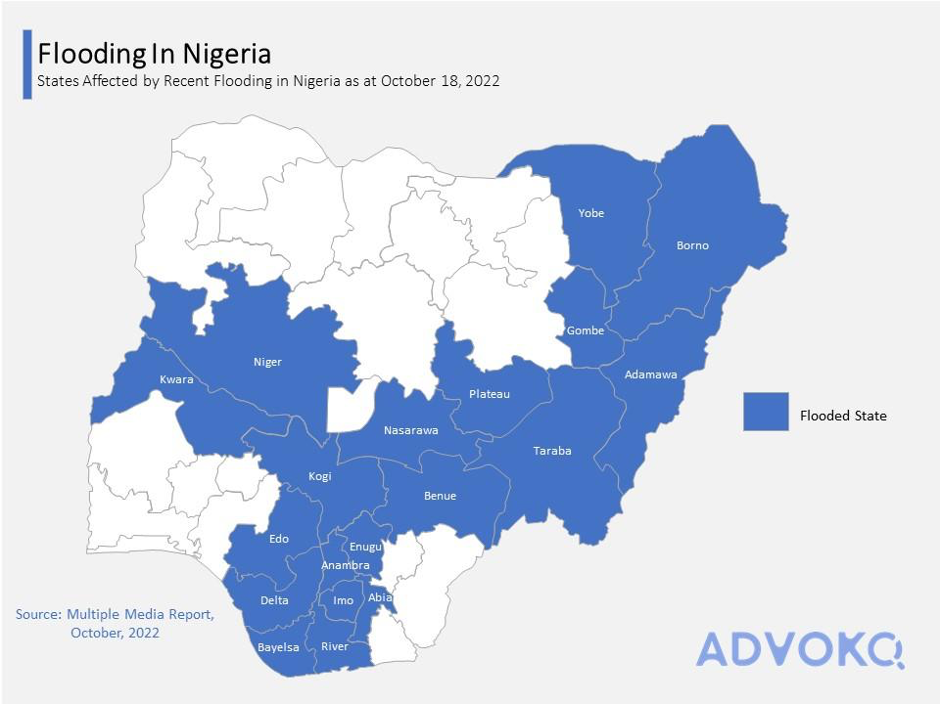

Already, flooding in the country in 2022 has displaced more than half a million people, according to the National Emergency Agency (NEMA). The Nigerian Metrological Agency (NiMet), in its September 2022 flooding outlook, noted that places that are along the course of River Niger and Benue have higher chances of experiencing flooding due to their present status. In August, states like Sokoto, Zamfara, Kaduna, Jigawa, Bauchi, Kano, Borno, Gombe, and Nasarawa recorded over 300mm (rainfall), a figure which represents over 25% of the long-term normal of the states in one month, this positioned them for an impending disaster as high-risk states as the year winds down.

More flooding, less attention

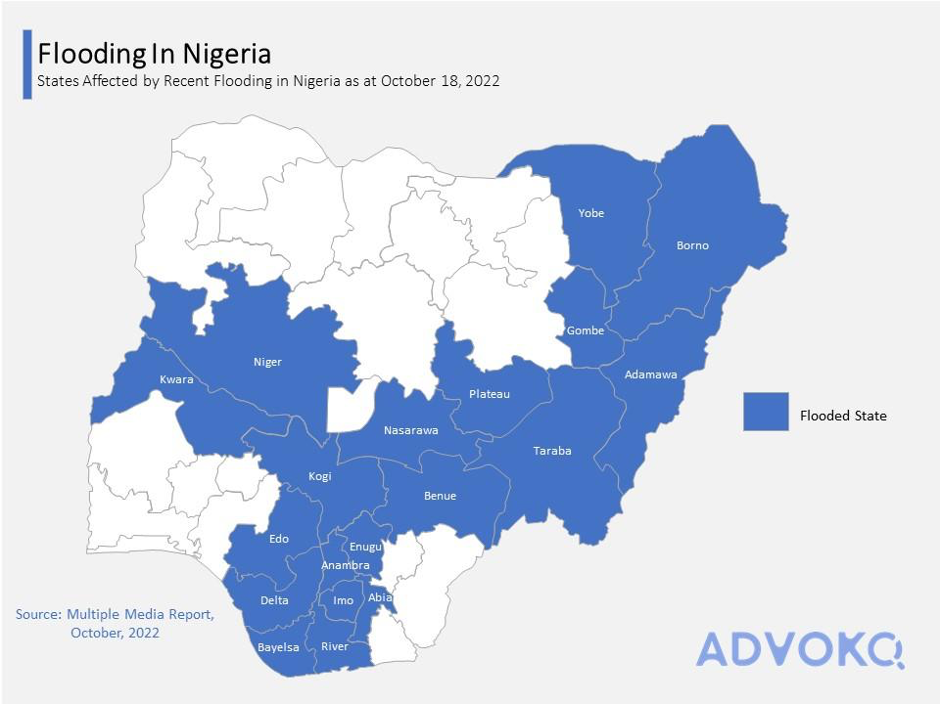

On 17 October, the flooding in Northern, and some parts of South Eastern, Nigeria entered the fourth week. While the number of casualties is yet to be known, houses have been underwater and citizens have been displaced.

Largely caused by the release of excess water from the Lagdo dam reservoir in the Republic of Cameroon on September, and torrential rainfall in the North-East, North-Central and Parts of South-Eastern part of the country, this flooding has put states along the course of River Niger and Benue at risk of flooding. The situation has further deteriorated with the wave of displacement and humanitarian crisis in the crisis-ridden northeast Nigeria. According to the International organization for Migration (IOM), there is urgent need for humanitarian assistance as over 15,000 internally displaced persons now scramble for shelter after their camps were destroyed by flooding.

Economically, analysts and social commentators are forecasting acute food shortage due to the negative impact caused by the flooding. Several reports have already confirmed that Olam Farm, a $140 million investment and Nigeria’s largest farmland of around 10,000 hectares in Nasarawa – one of the flooded states – has been taken over by this flood. Despite an intense effort from the Olam Farm to subvert the flooding, the farm’s 57 km dykes which were meant to prevent the farm from being flooded were broken thereby giving way for the running to submerge the 4,400 km hectare of rice currently on the farm.

With this huge loss, there might be a hike in the price of rice — one of the most consumed foods in the country. Currently, the movement of goods and important valuables has also been disrupted by the flooding as major roads in Lokoja, Kogi State capital remain flooded. This invariably has made movement from the North Central part to the Southern region of the country impossible for motorists and travellers.

Most unexplainable is the adverse effect of the flooding on small and medium-scale farmers in this region. In Benue, the food basket of the nation, farmers are already ruing the loss of their produce and are now seeking government support. In Adamawa, another state along the course of River Benue, it is alarming that 27,800 households and 89,342 hectares of farmlands have been affected by the flood. In Anambra, the number of flood victims is increasing daily as the flooding expands to more communities in the south-eastern state.

A way forward

Vulnerability to extreme climatic change in Nigeria is becoming more intense as accelerated urbanization continues to push more people into the capital cities in different regions of the country. In many of the states in the country, urbanization pressure across different urban areas is gradually expanding towns and cities to flood plains and coastal strips where they are exposed to more coastal flood risks. It is therefore important to curb further occurrences and build resilience to climate change by promoting planned human settlements and intensive urban infrastructural development. More importantly, the government must ensure that properties and lives in susceptible areas are protected through policy interventions and increased funding of climate-related projects.

To improve adaptation to climate-related disasters, Nigerian states, especially those along the coastal areas (Delta, Bayelsa, Anambra, Lagos, and Kogi) and flood plains, must be included in a wider and structured plan for climate change adaptation in the country. At the national level, the Great Green Wall Initiative and the Climate Change Act must be implemented as the country continues to battle desertification, food shortage, and climate change. Also, delayed implementation and financing of the Nigeria Climate Change commission has made it difficult for fragile states in the country to receive strong institutional support. Therefore, both state and non-State actors must ensure that this commission is properly funded to provide support to the country’s growing population.

More importantly, the stakeholders at the national and sub-national must prioritize the planning and implementation of effective green infrastructure as a way of enhancing environmental sustainability in Nigeria. For a country currently embroiled in the climate crisis, investing a considerable amount of public funds in green infrastructure and urban drainage may mitigate the risks posed by disasters.

In some instances, external funding by international organizations has been mismanaged by state actors thereby leaving people at risk of flooding every year. Therefore, policymakers, climate activists and urban planners must intensify debates on the government’s policy response to the climate-related disaster in Nigeria and identify its importance. The government must ensure it scales-up financing of urban infrastructure projects that address the survival of the people during flooding. Millions of lives and livelihoods are at stake if not.