Factcheck: 21 misleading myths about electric vehicles

By Simon Evans, Deputy Editor and Policy Editor, Carbon Brief | April 2, 2024

This article was first published by Carbon Brief in October 2023.

Electric vehicles (EVs) significantly cut lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions in almost all circumstances and are the key technology for decarbonising road transport.

While not having a car has even larger climate benefits, many peoples’ ability to go car-free is limited by their circumstances and the availability of alternatives.

This means EVs are “likely crucial” for tackling transport emissions, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

EV sales are growing fast, accounting for one in every seven cars sold globally in 2022 – up from one-in-70 just five years earlier.

Yet EVs are also being subjected to relentless hostile reporting across mainstream media in many major economies, including the UK.

Here, Carbon Brief factchecks 21 of the most common – and persistent – myths about EVs.

FALSE: ‘An EV has to travel 50,000+ miles to break even’

One of the most common false claims made against EVs is that they offer little or no climate benefit over conventional cars, due to the emissions associated with making their battery.

In a Twitter post promoting his anti-EV comment article for the Daily Mail, for example, the climate-sceptic former Conservative peer Matt Ridley claimed:

“An EV has to travel 50,000+ miles to break even with an ICE [internal combustion engine] car. That number is growing, not shrinking.”

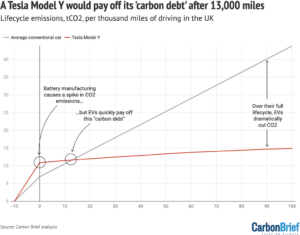

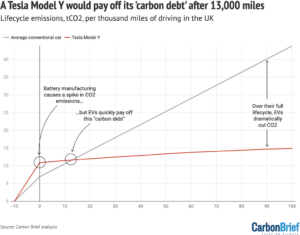

This is doubly false. As Carbon Brief showed in its 2019 factcheck, it takes less than two years for a typical EV to pay off the “carbon debt” from its battery. Over the full vehicle lifecycle, carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from an EV are around three times lower than an average petrol car.

In reality, therefore, an EV in Europe will pay off its carbon debt after around 11,000 miles (18,000km), according to the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

Moreover, the lifecycle benefits of EVs are increasing over time as electricity grids get cleaner.

In a 2021 lifecycle analysis, the ICCT found that an EV bought in Europe would cut emissions by 66-69%, relative to a conventional car. By 2030, this emissions saving would rise to 74-77%, the ICCT said, “as the electricity mix continues to decarbonise”.

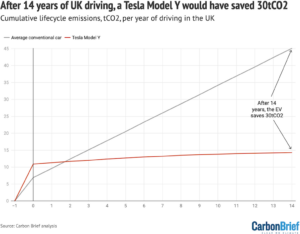

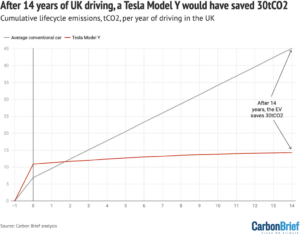

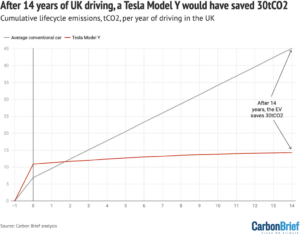

New Carbon Brief analysis shows that a Tesla Model Y, the world’s best-selling EV, would pay off its “carbon debt” after around 13,000 miles in the UK (21,000km), as shown in the figure below.

This would take less than two years for the average UK driver.

Lifecycle tonnes of CO2 (y-axis) per thousand miles of driving in the UK (x-axis) for a new Tesla Model Y (red) versus a new combustion-engine petrol car with EU-average fuel efficiency (grey). Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

Typically, claims to the contrary argue that the higher emissions created during production of an EV are only very slowly paid off, or perhaps not at all, during the vehicles’ full lifecycle.

Yet these claims almost always make the same three key mistakes, which serve to underplay the emissions from combustion-engine cars and overestimate those from EVs.

First, these claims routinely overstate the emissions associated with manufacturing EV batteries, often cherrypicking older studies with the highest estimates.

Second, they usually take fuel-efficiency figures at face value, ignoring the long-standing issue that vehicle test cycles are unrealistic – with real-world efficiency around 40% worse than stated.

(Combustion-engine car test cycles were the subject of deliberate manipulation exposed by the “dieselgate” scandal. While real-world EV mileage is also lower than in test cycles and some electricity is lost during charging, this only adds around 19% to energy use, according to the ICCT.)

Third, they generally ignore the significant amount of CO2 associated with fuel production, including refining, which adds at least 20% – or more – to that emitted from the car’s tailpipe.

Taking these together, the ICCT concludes that combustion-engine cars have lifecycle emissions that are “twice as high as official tailpipe CO2 values”.

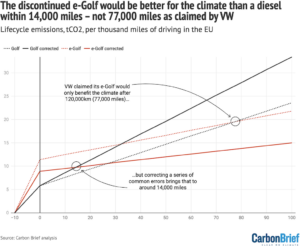

FALSE: ‘VW’s e-Golf becomes more environmentally friendly only after 77,000 miles’

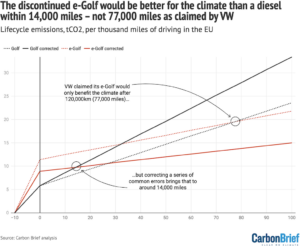

In order to support their false claims about the climate benefits of EVs, many articles refer to figures published several years ago by carmaker VW.

These studies have an air of credibility – after all, surely the manufacturers know best about their own supply chains? Yet both have been comprehensively – and repeatedly – corrected.

A few days before publishing Ridley’s false claims in July 2023 (see above), the Daily Mail published a news article including almost identical inaccuracies about the emissions benefits of EVs:

“The environmental benefit of electric cars may never be felt – with their production creating up to 70% more emissions than their petrol equivalent. Electric cars need to be used for tens of thousands of miles before they offset the higher releases, with VW’s e-Golf becoming more environmentally friendly only after 77,000 miles, according to the manufacturer’s own figures.”

There are several issues with these figures, including the fact that the e-Golf was discontinued three years ago. More substantively, the figures behind the VW analysis – shared with Carbon Brief in 2020 – show that the company makes the same key errors identified above. (See: FALSE: ‘An EV has to travel 50,000+ miles to break even’.)

Specifically: VW overestimates the emissions associated with making batteries; VW fails to account for the real-world fuel economy of its diesel Golf; VW underestimates the emissions associated with diesel fuel production; and VW overestimates the emissions in EU electricity.

Correcting for these errors shows that the e-Golf – if it were still being produced – would pay off its carbon debt after closer to 14,000 miles, or less than two years of UK average mileage.

Lifecycle tonnes of CO2 (y-axis) per thousand miles of driving in the EU (x-axis) for an e-Golf (red) versus a Golf diesel (black). Dotted lines show VW’s original uncorrected analysis. Solid lines show corrected estimates. Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

Carbon Brief and others corrected these figures from VW at the time – and they no longer appear on the VW website – yet they continue to be repeated in media attacks on EVs.

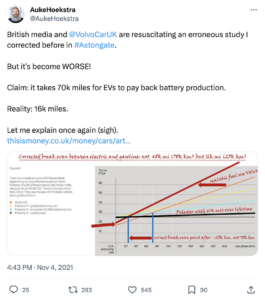

FALSE: ‘The electric Volvo C40 needs to be driven around 68,400 miles to cut carbon’

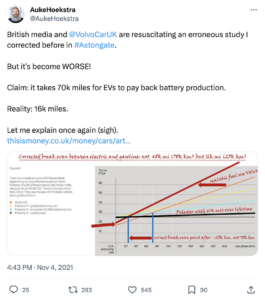

Newspapers have also continued to reuse estimates of the climate impact of Volvo’s EVs, published in 2021, which, as with those from VW, have been repeatedly corrected.

For example, a July 2023 article in the Daily Mail wrote:

“Volvo revealed in 2021 that the emissions from the production of electric cars can be up to 70% higher than petrol models and said it would require between 30,000 and 68,400 miles for an EV to become greener overall.”

This is recycled wording from the newspaper’s 2021 article, which had said:

“Volvo estimated that an electric Volvo C40 needs to be driven around 68,400 miles to have a lower total carbon footprint than its petrol equivalent, if the former is powered by the current global electricity mix.”

The Daily Mail’s repetition ignores a 2021 correction from Auke Hoekstra, a researcher at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU Eindhoven).

Hoekstra said Volvo overestimated the emissions in electricity generation, overestimated the fuel efficiency of its petrol car and underestimated the emissions associated with fuel production.

Overall, Hoekstra estimated that the Volvo C40 EV would pay off its “carbon debt” relative to a petrol XC40 after 16,000 miles, rather than the top-end 68,400 miles quoted by the Daily Mail.

Interestingly, Volvo itself says in its 2021 report that – even with its disputed figures – its C40 EV shows a “great reduction” in emissions compared with a petrol equivalent:

“The carbon footprint [of an electric C40 Recharge] shows a great reduction in greenhouse gas emissions compared to that of an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle.”

Elsewhere in the report, Volvo notes that its assumptions are “conservative” and that, for example, it is “highly probable” that the carbon intensity of electricity generation will improve rapidly during the lifetime of an EV, meaning its results are “likely to overestimate the total carbon footprint”.

The manufacturer also says: “Volvo Cars has committed to only sell fully electric cars by 2030.”

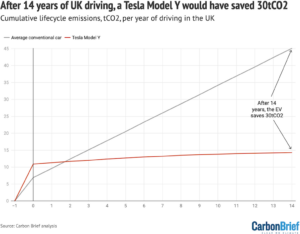

FALSE: ‘Electric vehicles have little or no CO2 advantage over the car you already drive’

Some newspapers have gone a step further in their attacks on EVs, falsely suggesting that they may not benefit the climate at all compared with combustion-engine cars.

The Daily Express gave climate-sceptic motoring lobbyist Howard Cox a July 2023 comment slot to argue: “Electric vehicles have little or no CO2 advantage over the car you already drive.”

As explained above, EVs cut lifecycle emissions relative to combustion-engine cars by around two-thirds in Europe – and this figure is expected to climb.

After an average petrol car has been driven for 14 years – the UK-average age at scrappage – its carbon footprint would be 45 tonnes of CO2 (tCO2), illustrated by the black line in the chart below.

In contrast, an electric Tesla Model Y would emit 14tCO2 – a saving of 30tCO2 or 68%. This is shown by the curved red line, with the Tesla’s annual impact falling as the grid is decarbonised.

Lifecycle tonnes of CO2 (y-axis) per year of driving in the UK (x-axis) for a Tesla Model Y (red) versus an average conventional car (grey). Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

Indeed, a petrol car driven a UK annual-average of 7,400 miles emits nearly 3tCO2 every year thanks to the emissions from burning its fuel. (This is based on 2019 average mileage, as driving distances have yet to recover to pre-Covid levels.)

For comparison, global CO2 emissions are an average of 4.7t per person per year, 5.1tCO2 in the UK and 14.9tCO2 in the US. The average for Africa is 1.0tCO2 per person per year.

In support of his false claim that EVs do not have an emissions advantage over combustion-engine cars, Cox cites a self-published report that his organisation, FairFuel UK, funded with the Alliance of British Drivers and the Motorcycle Action Group. No authors are listed.

The report’s references include the notorious climate-sceptic blogs Watts Up With That? and JunkScience, an article in the Jaguar Drivers’ Club in-house magazine, and the climate-sceptic lobby group the Global Warming Policy Foundation and its campaigning arm Net Zero Watch.

The report’s false assertions are at odds with analysis published by the IPCC, the ICCT, the British and US governments and many others.

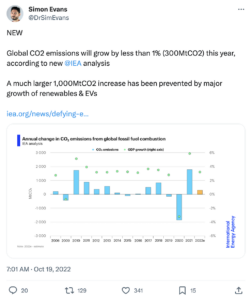

FALSE: ‘Climate change is accelerating because of the ban on combustion-engines’

German magazine Der Spiegel has published even more outlandish claims about EVs.

In an August 2023 article, it quotes the former head of the ifo institute Hans-Werner Sinn saying that “climate change is accelerating because of the ban on combustion-engines”.

The quote comes from an interview Sinn gave to German tabloid Bild. He argued that while EVs might reduce oil demand and emissions in one country, this is simply displaced elsewhere.

Notably, Sinn is contradicted not only by the expected climate benefits of EVs in the future, but also by the evidence of their emissions impact in the recent past.

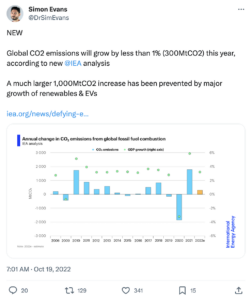

In an October 2022 analysis, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that EVs and renewable energy sources had prevented some 600m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) emissions last year. It said:

“The rise in global CO2 emissions this year [2022] would be much larger – more than tripling to reach close to 1bn tonnes – were it not for the major deployments of renewable energy technologies and electric vehicles (EVs) around the world.”

In separate analysis published in April 2023 and covered by Carbon Brief, the IEA said that the EVs sold in 2022 alone had cut global emissions by 80MtCO2.

The IEA added that, by the end of the decade, EV sales were on track to displace 5m barrels of oil demand per day – some 5% of the current total – and to cut annual global emissions by 700MtCO2, roughly the current yearly output of Germany or Saudi Arabia.

FALSE: ‘Old bangers are the green motorist’s choice’

Another common argument against the adoption of EVs is that keeping older cars – colloquially known in the UK as “bangers” – would be more environmentally friendly than buying a new model.

Writing in the Guardian in June 2023, for example, comedian Rowan Atkinson said that “keeping your old petrol car may be better than buying an EV”.

(The Guardian subsequently published a factcheck of Atkinson’s claims, including this one.)

Atkinson’s argument was supported by letter-writers to the Sunday Times, which published their missives under the headline: “Old bangers are the green motorist’s choice.”

A 2021 comment for the Daily Telegraph by assistant editor Jeremy Warner was more definitive:

“If you want to do your bit for the planet, forget Tesla and other super expensive electric vehicles; just carry on driving the same old gas-guzzling banger you’ve always had. As much if not more carbon tends to be expended producing a new car as actually driving it.”

Avoiding the premature scrapping of functioning vehicles makes financial sense. Indeed, this is embedded in government plans to ban the sale of new combustion-engine cars by 2035 or before.

(The UK government had pledged to ban new combustion-engine car sales from 2030, with hybrid vehicle sales allowed to continue until 2035. It has since pushed back the ban to 2035.)

Given a lifetime of around 15 years, a 2035 ban would ensure that combustion-engine cars are off the road by 2050, when CO2 emissions need to reach net-zero to limit warming to 1.5C.

Yet, perhaps counterintuitively, it would still be a net benefit for the atmosphere to retire an “old banger” early in favour of an EV, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Despite the bump in CO2 from manufacturing an electric car and its battery, a new EV would start cutting emissions after 20,000-32,000 miles in the UK (32,000-50,000km), per the chart below.

Lifecycle tonnes of CO2 (y-axis) per thousand miles of driving in the UK (x-axis) for an old pre-2015 petrol Ford Focus (grey), old pre-2000 petrol Mercedes (black), a new Tesla Model Y (red) or new Nissan Leaf (pink). Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

This means that an average UK driver replacing an “old banger” would pay off the carbon debt from buying a new EV within around four years, with the exact timelines depending on the fuel efficiency of the car being scrapped, annual mileage and the battery size of the new EV.

(The Sunday Times letter-writer driving a 36-year old Mercedes only 5,000 miles a year would start cutting emissions with a new Tesla Model Y after five years.)

FALSE: ‘EVs simply displace carbon emissions from roads to distant power stations’

A common refrain from those arguing that EVs are “nowhere near as green as you think”, in the words of climate-sceptic columnist Ross Clark in the Daily Mail, is that “driving an electric car simply displaces carbon emissions from roads to distant power stations”.

This argument is often misleadingly used to suggest that EVs are powered wholly or mainly on fossil fuels – with the implication that they are, therefore, unlikely to cut emissions. Clark says:

“If all the electricity used to power a car comes from coal – China and Poland, for example, have large numbers of coal power stations – you would need to drive 78,700 miles before your electric car’s carbon ‘budget’ broke even.”

First, there are no countries in the world that generate all of their electricity from coal. In China, the share of coal power was 61% in 2022, down 14 percentage points in a decade, with the equivalent figures in Poland being 69% and a reduction of 15 points.

Second, Carbon Brief analysis shows EVs would pay off their carbon debt in China and Poland after 22,000 miles (35,000km) and 18,000 miles (28,000km), respectively.

An academic analysis of EVs in China found they already cut carbon emissions by 40% relative to combustion-engine cars in 2020, with a further 43% reduction possible by 2030.

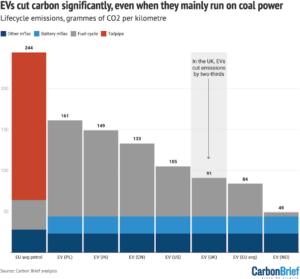

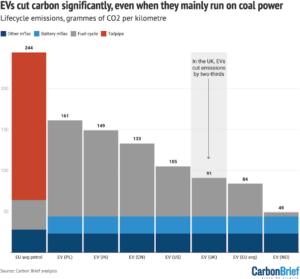

In general, EVs cut carbon emissions significantly, even if they mainly run on coal- or gas-fired electricity, as the chart below shows. In coal-heavy Poland, an EV would cut lifecycle emissions by two-fifths, Carbon Brief analysis shows, rising to two-thirds in the UK and four-fifths in Norway.

Lifecycle emissions, grams of CO2 per km, for an average EU petrol car and a Tesla Model Y running on the average electricity mix in a range of countries. Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

In its latest assessment report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) spelled this out, but added that EVs already cut emissions in almost all cases. It said:

“The extent to which EV deployment can decrease emissions by replacing internal combustion engine-based vehicles depends on the generation mix of the electric grid although, even with current grids, EVs reduce emissions in almost all cases.”

The IPCC went on to note that investments in EVs are “convertible” into low-carbon assets, even in countries with very carbon-intensive electricity:

“Today’s investments in electric vehicles in settings where electricity is produced with fossil fuels is an example of convertible investments – they will be decarbonised once electricity production has switched to renewable energies.”

The reason that EVs can cut emissions, even when running on fossil-heavy electricity, is that they are roughly four times more energy efficient than combustion-engine cars.

MOSTLY FALSE: ‘Electric cars are not green machines’

As noted above, many attacks on the climate benefits of EVs are completely false. Yet it is also the case that there is a non-trivial carbon footprint associated with the production and use of EVs.

For some commentators, this is an opportunity to make the perfect the enemy of the good, with a recent Daily Mail headline stating: “Electric cars are NOT green machines.”

When an EV bought in the UK today would cut emissions by two-thirds, relative to a combustion-engine car, it is obvious which is the “greener” choice.

Yet with a lifecycle carbon footprint of 20 or even 30tCO2, depending on lifetime mileage, location and the size of the EV battery, there is clearly scope for EVs to become lower-carbon in the future.

This is already expected to happen to some extent – as already noted – as electricity grids are decarbonised around the world. But mining, battery manufacturing and the production of steel, aluminium and other components all add to EVs’ footprint overall.

The IPCC says, with high confidence, that EVs running on low-carbon electricity “offer the largest decarbonisation potential for land-based transport, on a lifecycle basis”. But it also notes:

“Further efforts to reduce the GHG footprint of battery production…are essential for maximising the mitigation potential of BEVs [battery EVs].”

In other words, EVs are central to decarbonising road transport, but more needs to be done to ensure their production and use has the lowest-possible emissions.

The Daily Mail draws a different conclusion, continuing its headline by stating falsely:

“The environmental benefit of EVs may never be felt as their production creates up to 70% more emissions than petrol equivalents.”

While it is true that the production of EVs creates more CO2 than petrol equivalents – the US Argonne National Laboratory puts manufacturing-phase emissions at some 30-100% higher, depending on battery size – this carbon debt is paid off quickly. (See: FALSE: ‘An EV has to travel 50,000+ miles to break even.’) As a result, EVs still cut carbon significantly overall.

Moreover, the Argonne analysis says EVs’ production-phase disadvantage will shrink significantly by 2030-2035, falling to 5-50%, as supply chains become lower-carbon and more efficient.

It also notes the potential for steel decarbonisation to be a “major source of opportunity for emissions reduction” in the future – for example, using “green steel” produced without burning coal.

INCOMPLETE: ‘Electric vehicles alone can’t solve climate change’

Among all the myths about EVs, it can be easy to lose sight of one important point, summarised in the headline of a recent Bloomberg editorial: “Electric vehicles alone can’t solve climate change.”

On the one hand, this statement is trivially true, in the sense that it could equally be applied to any individual climate solution. On the other hand, this statement is also incomplete.

No serious strategy for decarbonising road transport – let alone the entire global economy – could rely on EVs alone. But this is hardly a reason to push back on the adoption of EVs.

Aerial photo of electric buses in east China. Credit: Imago / Alamy Stock Photo

On the contrary, the IPCC concludes that EVs are “likely crucial”. Its latest report says:

“Widespread electrification of the transport sector is likely crucial for reducing transport emissions.”

Indeed, the IPCC finds that EVs – along with other zero-carbon fuels – likely have the single-largest potential to cut transport emissions. Moreover, it puts the carbon-cutting potential of these technologies ahead of changes to urban infrastructure and behaviour.

The IPCC says EVs and other technological changes can contribute an estimated 50% of emissions cuts in the land transport sector by 2050, with a range of 30-70%. It says:

“Technology adoption, particularly banning combustion and diesel engines and 100% EV targets (and other zero-carbon fuels, especially in freight) and efficient lightweight cars, can contribute to between 30% and 70% of GHG emissions reduction from land transport in 2050, with 50% as our central estimate.”

This is well ahead of the potential from changes in urban infrastructure (30%, range 20-50%), behavioural change (5%, range up to 15%) and active travel (2-10%), according to the IPCC.

As a result, the IPCC concludes with high confidence that:

“Several end uses, such as passenger transportation (light-duty electric vehicles, two and three wheelers, buses, rail)…are likely to be electrified in net-zero energy systems.”

Nevertheless, the IPCC makes clear that other options for cutting transport emissions are an important part of the solution for reaching net-zero emissions globally.

On urban infrastructure, the IPCC says:

“Infrastructure use (specifically urban planning and shared pooled mobility) has about 20-50% (on average) potential in land transport GHG emissions reduction, especially via redirecting the ongoing design of existing infrastructures in developing countries, and with 30% as our central estimate.”

On behaviour change, the IPCC says:

“[S]ocio-cultural factors can contribute up to 15% to land transport GHG emissions reduction by 2050, with 5% as our central estimate. Active mobility, such as walking and cycling, has 2-10% potential in GHG emissions reduction.”

(At a household level, the IPCC cites findings showing that “liv[ing] car-free” is the single-most effective individual action, with the potential to cut emissions by around 2tCO2 per person per year. Shifting from a combustion-engine car to an EV would have a similar impact, it notes.)

Overall, it is clear from the IPCC report that EVs are “crucial” to decarbonising transport, but also that they cannot do the job alone. In addition, EVs will only reach their full carbon-cutting potential if electricity systems and manufacturing supply chains are also decarbonised.

FALSE: ‘EVs are [low-mileage] runabouts…[that] take a long time to pay off their carbon debt’

In a July 2023 article for the Daily Mail, climate-sceptic columnist Ross Clark falsely claims that EVs will take a long time to pay off their “carbon debt” of manufacturing, because they are mostly “used as runabouts in towns and cities”.

He asserts, without evidence, that the mileage of EVs is low due to “their limited range”. A cursory glance at real-world data shows these claims to be false.

New EVs in the UK drive an average of 9,435 miles per year in the first three years of their life, according to analysis of MOT data from the RAC Foundation. This is well above the average for UK cars overall and 26% further than the average new petrol car, the analysis finds.

(The figures also show new diesels covering 12,496 miles per year. However, diesel cars are rapidly becoming less popular, accounting for less than 4% of sales in 2023 to date.)

Figures from Norway paint a similar picture. EVs now drive more miles each year, on average, than petrol or diesel cars, according to the latest official figures discussed by BloombergNEF head of transport Colin McKerracher in an article for Bloomberg. He writes:

“This effect shouldn’t be surprising; people like to use more of things that are cheaper. But it wasn’t always received wisdom in the market. A few years ago, some oil energy outlooks assumed not only that EV adoption would be muted, but that each EV would on average travel less than a comparable internal combustion vehicle. This now looks like a very shaky assumption…at BNEF, we’re expecting this same effect to start showing up in the data of more countries in the years ahead.”

FALSE: ‘Synthetic petrol could displace electric vehicles’

In early 2023, an EU rule banning the sale of new combustion-engine cars from 2035 was delayed by several weeks after Germany insisted on an exemption for cars running on “e-fuels”.

Sometimes referred to as “synthetic fuels”, they are made by combining CO2 with hydrogen and can be used in existing combustion-engines. If they are made with low-carbon hydrogen, synthetic fuels can have a low carbon footprint overall.

These apparent advantages have persuaded some politicians and commentators to argue for their widespread use, with some going so far as to suggest they could “stop electric cars in their tracks”.

For example, in a since-corrected comment for the Guardian, comedian Rowan Atkinson argued that “a sensible thing to do would be to speed up the development of synthetic fuel”.

In March 2023, the UK parliamentary select committee on transport also argued in favour of using synthetic fuels, in a report that received positive media coverage, stating:

“[D]rop-in sustainable fuels enables us to address the existing fleet and minimise cost (and carbon emissions) through the use of existing infrastructure. It would also enable more socially equitable access to carbon reduction technologies for everyday transport as it would not be necessary to buy a new electric car and have access to charging infrastructure.”

The recent interest in synthetic fuels has been co-opted by those seeking to delay the UK government’s pledged ban on sales of new combustion-engine cars.

Such calls, including lobbying from the UK’s fuel producers, were rejected by the government on the basis that synthetic fuels are “expensive”, “not proven” and contribute to air pollution.

Synthetic fuels are indeed costly. They are ”up to three times more expensive than conventional fossil fuels”, according to the IPCC, and “expensive…even in the long run”, says the IEA.

They are also very inefficient to produce. Carbon Brief analysis shows it would take at least five times as much electricity to run cars on e-fuels as for EVs.

EVs running on renewables also have significantly lower CO2 emissions than cars burning e-fuels made from the same source of power, according to lifecycle analysis for the UK government.

(According to NGO Transport & Environment, lifecycle emissions from an EV in 2030 would be 53% lower than for a combustion-engine car running on e-fuels.)

These issues make it vanishingly unlikely that synthetic fuels will “displace” EVs, let alone “stop electric cars in their tracks”. The IPCC explains that synthetic fuels will be relatively scarce and expensive, with their use focused on harder-to-abate sectors such as aviation. It says:

“Given these high costs and limited scales, the adoption of synthetic fuels will likely focus on the aviation, shipping and long-distance road transport segments, where decarbonisation by electrification is more challenging.”

Indeed, the head of German airline Lufthansa recently pushed back against the use of synthetic fuels for cars. Referring to moves by luxury carmaker Porsche to get exemptions from combustion engine bans based on e-fuels, he said:

“With no technology in sight to replace fuels, we really need all the sustainable aviation fuel in the world…[Porsche chief executive] Oliver [Blume] can maybe have some for his 911, but we really need the volumes.”

Mercedes-Benz chief executive Ola Källenius, at least, has acknowledged this reality, stating: “As for carbon-reduced fuels…aviation will need them.”

A 2021 briefing from Transport and Environment concluded bluntly: “E-fools: why e-fuels in cars make no economic or environmental sense.”

A June 2023 article for the Evening Standard was titled, “Synthetic petrol could displace electric vehicles” – but went on to undermine its own headline. The piece asked: “Could e-fuels completely derail attempts to phase out the internal combustion engine?” It then answered: “[T]here’s no suggestion e-fuels are a credible like-for-like replacement for today’s petrol use.”

FALSE: ‘Hydrogen cars are more sustainable than EVs’

Hydrogen cars are another favourite of those disputing the benefits of EVs. In his Guardian article criticising EVs, for example, Rowan Atkinson said hydrogen was an “interesting alternative fuel”.

Elsewhere, a recent feature in the Times is titled: “Hydrogen cars were the future once – might they be again?” Going a step further is an article from “sustainable living” website the Ethos, which claims falsely that “hydrogen cars are more sustainable than EVs”

In a since-deleted article for the Daily Express, the founder of a firm hoping to make hydrogen from waste plastic writes glowingly of its potential and says that EVs are “destined to go the way of the dodo”.

The evidence, however, paints a very different picture, both in terms of the prospects for hydrogen versus electrified transport and when it comes to their relative sustainability.

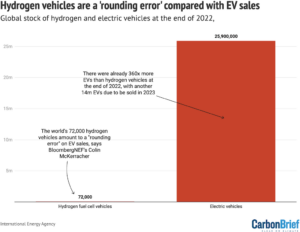

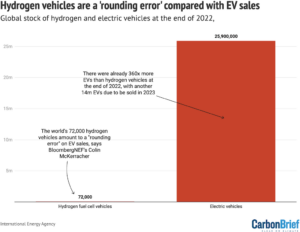

There were only 72,000 hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles on the planet at the end of 2022, against 26m EVs, according to the IEA. This means there were already 360 times more EVs than hydrogen vehicles at the end of 2022, as shown in the figure below.

With EV sales set to climb by 40% to 14m units in 2023 and hydrogen vehicle sales falling, this chasm is set to widen even further.

Global stock of hydrogen fuel cell and battery electric vehicles at the end of 2022. Source: IEA global EV outlook 2023. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

According to Colin McKerracher, head of advanced transport for BloombergNEF, fuel-cell vehicle sales are “a rounding error” relative to sales of EVs, despite the fact that governments have “bent over backwards to make their support as technology-neutral as possible”. He writes:

“A dearth of government support isn’t the issue for alternatives to battery EVs – the problem is the product. Fuel cell vehicles are failing because they’re not proving compelling enough.”

As to the false idea that hydrogen cars are more sustainable than EVs, this is at odds with the findings of a lifecycle analysis for the UK government.

This analysis found that EVs are “much more efficient” than hydrogen cars, using only a third of the energy. It also said lifecycle emissions from hydrogen cars would be 60-70% higher than EVs, even assuming that the hydrogen was from low-carbon sources.

The latest IPCC report concluded that EVs are “the most attractive” option for cars, whereas hydrogen vehicles could “complement” EVs in heavy-duty transport.

FALSE: ‘Sales of electric vehicles appear to be slowing’

One bizarrely persistent myth is that consumer appetites are turning away from EVs. An October 2022 article in the Times, for example, said that “sales of electric vehicles appear to be slowing”.

This is false: indeed, EVs sales are surging in the UK and globally. Yet a September 2023 Times article said the “popularity of electric cars (EVs) continues to wane”.

The Daily Telegraph’s climate-sceptic columnist Matthew Lynn may have marked the apogee of this trend with a comment headlined: “Nobody wants an electric car”. (Lynn also wrote in a 2007 article for the New Zealand Herald that the iPhone “won’t make a long-term mark on the industry”.)

It is easy to see why some newspapers and columnists have been blindsided by the pace of change. In 2017, only one in every 70 new cars sold was an EV (1.4%). Just five years later, in 2022, this had risen to one in seven (14.4%), according to figures from the IEA.

In April 2023, the IEA said “explosive” growth would see EVs making up 18% of global car sales in 2023, just two years after saying that threshold would not be crossed until after 2030.

A slow initial phase followed by increasingly rapid growth is characteristic of the “S-curve” of technology adoption, which has been followed by mobile phones and now EVs.

In the UK, EV sales grew 88% in July 2023 compared with the same month a year earlier and 72% in August. Some 16.4% of sales in the first eight months of 2023 were “pure” EVs with no combustion engine, up from 14.0% in the same period of 2022.

The UK has also seen rapid expansion in the second-hand market for EVs, which grew by 81% in the second quarter of 2023, albeit from a low base.

Forecasts from industry group the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) show pure electric cars and vans roughly doubling and tripling their shares of sales, to 22.6% and 11.2%, respectively, between 2021 and 2024. This would put them on track to meet the requirements of the UK’s recently confirmed “zero emissions vehicle” (ZEV) mandate, which enters force in 2024.

The world’s top 10 markets for EVs all saw double-digit growth in sales during the second quarter of 2023, Bloomberg reports, including China, the US, Germany and France.

While there is a wide range of views over how quickly the shift to EVs will happen, even oil producers’ cartel OPEC agrees that their sales and market share will grow rapidly.

The IEA says EVs will make up a third of global car sales by 2030, with BloombergNEF saying 45%. The most aggressive recent forecasts for EVs come from the Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) and use S-curves to predict a global EV share of 60-80% by 2030.

For context, some 37% of car sales in China in August 2023 were EVs or “plug-in” hybrids, BloombergNEF says.

FALSE: ‘Electric cars could soon be more expensive to drive than their petrol equivalents’

One of the most obvious advantages of electric cars is their much lower running costs, relative to combustion-engine equivalents. This is largely a result of their far greater efficiency.

In an October 2023 article, the UK’s Climate Change Committee (CCC) says EVs “will be significantly cheaper than petrol and diesel vehicles to own and operate over their lifetimes”.

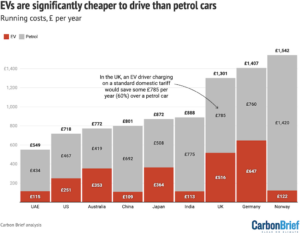

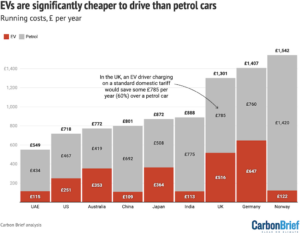

Indeed, Carbon Brief analysis shows that EV drivers would make significant savings over using a petrol car in all countries considered, from Australia to Argentina and from China to India, the US, or the UK. Annual EV savings, for a selection of these countries, are shown in the figure below.

Yet a number of newspaper articles have sought to paint a different picture.

In August 2022, for example, the Daily Telegraph reported: “Electric cars could soon be more expensive to drive than their petrol equivalents amid soaring energy prices.”

This supposed future – when EVs “could soon be more expensive to drive” – never came to pass.

The chart below illustrates the lower fuel costs of EVs in a varied range of countries, including COP28 host the UAE, as well as the US, China, India, UK and EV frontrunner Norway.

For each country, the chart shows annual fuel costs for an EV in red, based on standard domestic electricity prices as of mid- to late-2023, depending on data availability. This is compared with the equivalent annual cost for a petrol car in grey, based on pump prices in October 2023.

Annual fuel costs for an EV versus a petrol car in selected countries, based on standard domestic electricity prices in mid- to late-2023 and October 2023 pump prices. For the purposes of comparison, annual mileage and fuel efficiency is the same for all countries, based on figures for the EU. Source: Carbon Brief analysis. Chart by Carbon Brief using Datawrapper.

More recently, in July 2023, the Daily Mail published a similar article questioning the cost savings of EVs. However, it made a narrower and much more carefully worded claim. It said: “Recharging electric cars at public points can now prove more expensive than a petrol refill.”

In the UK at least, this can be true, depending on the fuel efficiency of the petrol and electric cars, the prevailing price of fuel and the type of public charge point used, given fast chargers are more expensive than home charging. Nevertheless, the statement is incomplete – and, therefore, potentially misleading.

Crucially, the majority of UK homes have access to off-street parking and owners usually charge their EVs overnight, using off-peak tariffs that are cheaper than standard home electricity prices.

While EVs cost significantly less to drive than petrol cars, they generally remain more expensive to buy. This is despite rapid declines in the cost of batteries over the past decade.

The IPCC’s latest report said that EV costs “are decreasing”. In its latest 2023 EV outlook, research firm BloombergNEF said price parity with combustion-engine cars “is getting closer”.

The outlook explained:

“EV price parity is getting closer, but progress varies by segment and country. Prices for lithium-ion batteries increased for the first time in 2022 and are likely to remain elevated in 2023. This delays the upfront price parity of battery electric vehicles with combustion cars. Despite the near-term increase, EVs still reach up-front price parity with comparable combustion vehicles, without subsidies, by the end of the decade in most segments.”

The outlook shows EVs reaching up-front price parity with combustion vehicles in the SUV and large car segments in Europe by 2025, with small and medium cars following by 2028.

(According to data firm Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, lithium-ion battery prices dipped below $100 per kilowatt hour in August 2023 for the first time since two years earlier.)

While they have yet to reach up-front price parity, the total cost of ownership of EVs reached parity with combustion-engine cars “in leading markets outside the US in the early 2020s”, according to RMI, thanks to lower running costs. Similarly, a recent analysis for the German government found “clear advantages for electric cars”, when looking at the total cost of ownership.

More recently, Bloomberg published a chart, below, showing that Tesla’s Model 3 and Model Y are now cheaper than the average selling price of a new car in the US.

(In October 2022, the Sun was among newspapers giving coverage to a woefully wrong analysis of the costs of the shift to EVs, commissioned from motoring campaign group Fair Fuel UK from economic consultancy the Centre for Economics and Business Research. In order to reach its paid-for conclusions, the consultancy incorrectly claimed that EVs cost more to run than petrol cars and makes the “simply perverse” assumption that the upfront cost of EVs would never change.)

FALSE: ‘There are insufficient raw materials…for all vehicles to be EVs’

Another common line of attack against the widespread adoption of EVs relates to the metals needed to make lithium-ion batteries.

In a March 2023 report, for example, the transport select committee of MPs in the UK parliament claimed – falsely – that “there are insufficient raw materials…for all vehicles to be EVs”.

This assertion does not appear to be supported by any evidence in the committee’s report. It also stands in stark contrast to the findings of the Energy Transitions Commission (ETC), which said in a July 2023 report that there was “no fundamental shortage” of any key materials. It said:

“There is no fundamental shortage of any of the raw materials to support a global transition to a net-zero economy: geological resources exceed the total projected cumulative demand from 2022-50 for all key materials, whether arising from the energy transition or other sectors.”

Writing in the Financial Times on the launch of the report, ETC chair Adair Turner said “myths” were “clouding the reality of our sustainable energy future”. He said it was important to separate those myths from genuine concerns and added:

“One thing we don’t need to worry about is long-term supply: for all the key minerals, known resources easily exceed total future requirements.”

It is clear that the shift to EVs will significantly increase demand for a number of “critical minerals”, including lithium, but also nickel, cobalt and others.

The IEA, for example, says that demand for critical minerals would grow by three-and-a-half times between 2023 and 2030 to reach 30m tonnes a year, if countries get on track to limit warming to 1.5C. It adds that EVs and batteries would be the main drivers of this demand growth.

In its July 2023 critical minerals market review, the IEA highlights the need to address mining environmental impacts, as the shift towards net-zero drives demand for minerals. It says:

“The mining industry has been associated with a host of negative environmental, social and governance (ESG) impacts, including human rights violations, contribution to armed conflict, environmental contamination, deforestation and other harms. Failure to manage these impacts could have profound implications for clean energy transitions as well as damage the environment and communities in the vicinity of mining deposits.”

These issues have prompted a torrent of media coverage, with headlines including one in the Daily Telegraph saying: “The green revolution is fuelling environmental destruction.” Elsewhere, the Washington Post ran a series of articles in early 2023 with the tagline “clean cars, hidden toll”.

Such coverage generally fails to offer perspective on the scale of resource extraction needed to support the world’s current fossil-fueled economy.

Some 15bn tonnes of fossil fuels are extracted and burnt each year. Under a 1.5C pathway, critical mineral needs would be 500 times lower, reaching 30m tonnes a year by 2030.

Making a similar point, Turner writes in his Financial Times article:

“Mineral supply challenges must be clearly faced and managed. But we must also welcome the sustainable nature of the new energy system. In today’s energy system, each year we burn 8bn tons of coal, 35bn barrels of oil, and 4tn cubic metres of gas, producing around 40bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent. In the new system, we extract far smaller quantities of key minerals and place them in structures that generate, store and use clean electrical energy; and the materials are then ready to do the same again next year or to be recycled over and over again. This is an inherently renewable system and the faster we build it the better.”

Turner also says that, setting aside the “myths”, there are “three key challenges” around critical minerals. These include scaling up supply fast enough to meet rising demand and diversifying supply chains, which are currently concentrated in a small number of countries.

His third challenge is the environmental impacts of mining:

“[N]ew developments can have adverse local environmental effects. In aggregate, the adverse effects will be more than offset by putting a stop to coal mining but that won’t be true for some local communities. Best mining and refining practices can dramatically reduce harm – and must be required by regulation imposed on mineral producers and users.”

FALSE: The lifetime of EV batteries is ‘horribly uncertain’

Over the years, many newspaper articles have raised questions over the longevity of EV batteries. Back in 2010, a Daily Telegraph article said the lifetime of batteries was “horribly uncertain” and predicted that this would make EVs “financially disastrous”.

In fact, most manufacturers offer battery warranties of at least eight years – and EVs do not depreciate any faster than conventional cars.

Still, even carmakers acknowledge that – perhaps not surprisingly – consumers remain uncertain about battery life, with Chinese-owned UK brand MG stating on its website: “Electric car battery life is one of the main factors that makes drivers reluctant to switch to an electric vehicle.”

UK motoring website Autocar notes that there are many “rumours and anecdotes” circulating about EV batteries failing “after a relatively short space of time”. It points to peoples’ experience with mobile phone batteries as one reason why such ideas persist.

However, Autocar goes on to say that most batteries will last the lifetime of the car. (Tesla says its batteries are “designed to outlast the vehicle”.) Autocar says:

“[T]he more electric cars that are out there and the longer they are run for, the more evidence is produced to show that the power pack will often last the lifetime of the car.”

A study of 15,000 EVs by Seattle-based battery analysis firm Recurrent Motors found that only 1.5% of batteries had been replaced. According to coverage of the study in the Globe and Mail, 90% of the cars that had covered over 100,000 miles still had at least 90% of their original range.

In a 2022 interview with Forbes, Nissan UK marketing director Nic Thomas is quoted saying:

“Almost all of the [electric car] batteries we’ve ever made are still in cars…And we’ve been selling electric cars for 12 years…It’s the complete opposite of what people feared when we first launched EVs – that the batteries would only last a short time”

UK roadside assistance firm RAC says: “For all intents and purposes, the lifespan of EV batteries…is broadly comparable to that of a traditional combustion car.

FALSE: ‘Electric vehicles can explode – petrol ones only do it in movies’

In a July 2023 article for the Sun, climate-sceptic motoring journalist Jeremy Clarkson wrote that EVs were “bloody dangerous”, as part of a lengthy and familiar list of their supposed issues.

His comment piece ran under the false and – presumably – tongue-in-cheek headline: “Electric vehicles can explode – petrol ones only do it in movies.”

If this was meant as a joke, it fell flat. It was also flat-out wrong. Indeed, the evidence does not support Clarkson’s viewpoint at all – quite the opposite.

Figures from Norway, where more than a fifth of cars on the road are electric, show that standard combustion engine vehicles catch fire around five or six times more often than EVs.

Emergency services were called to around 30 fires per 100,000 standard cars on the road per year during 2018-2022, compared with around five EV fires per 100,000 vehicles, according to the data compiled by Robbie Andrew of the Cicero climate research institute in Oslo, using figures from the Norwegian Directorate for Civil Protection and Emergency Planning (DSB) and Statistics Norway.

In a Twitter thread, Andrew translates reporting from Norway saying that EV fires rarely involve the battery and that, asked by a journalist how much people should “fear” fires in electric cars, the senior engineer at DSB says: “To a very, very small extent.”

(Andrew notes that the discrepancy could be partly down to the EV fleet being relatively new on average. He has previously pointed to major flaws in a widely shared study, from price comparison website AutoinsuranceEZ, which claimed to show that EVs suffer fewer fires than other cars.)

Several other sources confirm that EVs are much less likely to catch fire than combustion-engine vehicles. For example, Australian EV news site the Driven cited figures from the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency: “Petrol and diesel cars 20 times more likely to catch fire than EVs.”

Such is the interest in supposedly widespread EV fires, however, that certain media outlets have ended up falsely blaming the vehicles for fires they did not cause.

For example, the Daily Telegraph was one of several publications reporting a cargo ship fire in July 2023 as being “linked” to electric cars on board. On the day of the fire, on the Fremantle Highway car transporter ship in the North Sea, website electrek spoke to the Dutch coastguard and reported that – in contrast to widespread finger-pointing at EVs – the cause of the fire was unknown.

One month later, German trade publication Automobilwoche went further and reported that the fire had not been caused by exploding electric cars, “contrary to much media speculation”.

In a post on LinkedIn summarising its reporting, the outlet says: “The investigations indicate that the electric cars on board were not the cause of the fire, contrary to much media speculation.”

In July 2023, an EU-funded research programme on reducing the risk of fires on ships, known as LASH FIRE, released information on “facts and myths about fires in battery electric vehicles”.

There are fewer fires in EVs than in combustion engine cars, it says, adding that those fires that do occur in EVs do not burn more intensely or at higher temperatures than for combustion engines.

In summary, EVs are “not more hazardous” than conventional cars, the document says, but the risks they present are different. It explains:

“New technologies naturally raise a large interest in the public and as new energy carriers make their way into the market, some misconceptions will naturally also make their way to the public. BEVs are not more hazardous than internal combustion engine vehicles (ICEVs), but the risks of Li-ion batteries differ to those of conventional fuels.”

An August 2023 press release from the International Union of Marine Insurers comments on the Fremantle Highway fire and says: “to date, no fire onboard a ‘roro’ or pure car and truck carrier (PCTC) has been proven to have been caused by a factory-new EV”.

It reiterates the LASH FIRE findings and notes that while batteries exposed to fire can result in “thermal runaway”, which can be harder to put out, the resulting risks can be managed. It adds:

“Traditional fuels such as petrol and diesel are potentially extremely dangerous but we, as a maritime industry, have learnt to understand and mitigate the associated risks. Lithium-ion batteries are still relatively new but have already become a major part of everyday life. The maritime industry is still learning and needs to adapt to these new sets of risks and mitigate them accordingly.”

In another recent incident, social media users – and some media outlets – pointed the finger at EVs after a huge fire broke out in a car park at Luton airport in the UK.

Even after the local fire service “confirm[ed] the initial vehicle involved in the fire was a diesel car” and CCTV footage emerged of the car itself, showing it to be a 2014 diesel Range Rover, many social media users continued to insist that EVs must have been to blame.

Armchair experts argued that it is hard to get diesel to burn and that it must have been an electric hybrid, even though Range Rover did not sell hybrids in 2014. (An error-strewn 18 October comment by Daily Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson repeated this false claim.)

Meanwhile, the Daily Mail reported that there had been previous fires involving Range Rovers and Land Rovers. It said:

“The Range Rover fire which sparked last night’s Luton airport car park inferno comes six years after a Land Rover went up in flames at Liverpool’s Echo Arena’s car park. The blaze at Luton airport yesterday also comes six months after Land Rover recalled several models of the Range Rover and Range Rover Sport to address issues that could potentially lead to fires.”

FALSE: ‘Under Biden’s electric vehicle mandate, 40% of US auto jobs will disappear’

Another angle of attack on EVs is that the transition towards electrified transport will cause problems for the manufacturing industry in general and for its workers in particular.

In remarks reported by the Economist, for example, former US president Donald Trump said the shift to electric cars is a “transition to hell” that will destroy “your beautiful way of life”.

Yet, as a September 2023 article from CNN notes, the US car industry has announced more than $100bn of investment in the transition to EVs, creating “more than 100,000 American jobs”.

In further recent remarks, Trump falsely claimed that “under Biden’s electric vehicle mandate, 40% of US auto jobs will disappear”. FactCheck.org “found no support” for this claim.

Former President Donald Trump tours Drake Enterprises, an automotive supply company, in Michigan state. Credit: Associated Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

A New York Times factcheck also says Trump’s claim “lacks evidence” – but it repeats the idea that “electric vehicles can be made with fewer workers than gasoline vehicles”.

An article for Heatmap challenges this argument, saying that, while it seems to be “conventional wisdom”, research uncovered for the article “suggested the opposite”. It says:

“Trump may be exaggerating, but the underlying idea, that electric vehicles require less labour to manufacture than internal combustion engine cars, is the conventional wisdom. It has been circulated for years by automakers, autoworkers, politicians, and journalists. EVs contain fewer parts, the thinking goes, so naturally they will require fewer workers.

“That logic seems obvious, which might be why it hasn’t received much scrutiny. But when I tried to find any research supporting it, what I found instead suggested the opposite. A number of analyses showed that electric vehicles could actually require more labour to build than gas-powered cars in the US, at least for the foreseeable future.”

A 2020 report from the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) supports Heatmap, stating:

“The common wisdom that BEVs are less labour intensive in assembly stages than traditional vehicles is inaccurate. In fact, the labour requirements for assembling BEVs and ICEVs are comparable.”

In its latest report on how to limit global warming to 1.5C, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says that a shift towards net-zero emissions would see 30m new clean energy jobs created by 2030 in industries including low-carbon power and electric vehicles.

These new jobs would outweigh losses in coal, oil and gas extraction, as well as in the production of combustion-engine vehicles, by two to one overall, the IEA says. In the car industry specifically, the IEA suggests new jobs making EVs and batteries would roughly balance losses elsewhere.

Evidence from the UK suggests the shift to EVs could create 80,000-100,000 new jobs. However, these jobs are contingent on attracting manufacturers to make EVs and their batteries in the UK.

In a May 2023 report, government advisory body the CCC highlights the conditionality on these jobs:

“The UK has taken steps to capture market shares and some car manufacturers are investing in electric vehicle manufacturing in the UK. However, there have been challenges and there is a risk manufacturing will find more favourable conditions elsewhere. Subsidies in places such as the US and the EU are likely to attract investment and secure jobs outside of the UK.”

What is not in doubt is that the transition to electrified transport will be disruptive. The rise of Chinese manufacturers of EVs – and the batteries that power them – is a case in point.

Another BCG report, looking at the car industry in Europe out to 2030, notes that it expects the shift to EVs to have a “minor net impact” on job numbers overall. However, it adds that this “obscures massive changes” in the type and distribution of jobs in the sector.

In the US, the argument over EV jobs has coincided with – and is partially tied up in – a dispute between carmakers and unionised labour. In October 2023, the Financial Times reported:

“General Motors has agreed to include battery manufacturing plants in its overarching contract with the United Auto Workers [UAW], the union said, meeting a crucial demand for employees anxious over the industry’s shift to electric vehicles…The UAW has been pushing for higher wages and other concessions in a new contract…It has also sought to extend contract protections at the plants that will provide many of the batteries for a wave of EVs hitting the market in the next several years.”

FALSE: ‘Electric car revolution at crisis point’ due to ‘charging point shortage’

In early 2023, the Daily Mail reported that the “electric car revolution [is] at crisis point” in the UK due to a “charging point shortage”. Around the same time, the Times said a “lack of [charging] infrastructure” was “threatening the EV revolution”.

Since then, UK EV sales have continued to surge, growing 36% year-on-year in the first nine months of 2023. Global EV sales grew 40% in the first half of the year.

While the headlines are clearly false, it is clear that a rapid transition to EVs will require a similarly fast rollout of charging infrastructure – and there are bound to be teething troubles along the way.

In its sixth assessment report, the IPCC emphasises the need for investment in charging infrastructure and the electricity networks it connects too. It says with high confidence:

“The continued growth of electromobility for land transport would require investments in electric charging and related grid infrastructure.”

Returning to the case of the UK, the number of public charging points reached the milestone of 50,000 in early October 2023, according to charging services provider Zapmap. It said this represented year-on-year growth of 43%, with the number of “ultra-rapid” chargers up 68%.

Zapmap says the number of public chargers will reach 100,000 in 2025, if current rates of installation continue, against a government target of 300,000 by 2030.

While the number of chargers remains highest in London, recent growth has largely been outside the capital city, according to figures released in July 2023 by the Department for Transport.

In August 2023, the Association for Renewable Energy and Clean Technology (REA) and several other groups wrote to UK transport minister Jesse Norman, calling for charge points to be given priority in the queue for connections to the electricity grid, among other changes. They wrote:

“By adopting the recommendations in this report, the government can achieve its target of reaching 300,000 charge points by 2030, creating new jobs and driving economic growth.”

Nevertheless, a July 2023 editorial in the Times said: “The rollout of charging infrastructure is going too slowly.”

That month, the Financial Times reported industry fears the shift to EVs was being “held up” by the “painfully slow” process for connecting new chargers to the grid.

Looking at the global picture, some $1tn of investment in the charging network is needed over the next three decades, according to BloombergNEF. It explains:

“Over $1tn in cumulative investment in EV charging infrastructure is required globally over this period [to 2050]…The required charger investment is still small compared to overall auto sales. For example, China requires $453bn of cumulative investment in charging infrastructure to 2040, compared to automotive sales revenue from domestic car sales and exports of $750bn in 2022 alone.”

The number of public charge points more than doubled in several European countries over the past year, according to figures assembled by consultancy Cornwall Insight. Growth in the UK was in the middle of the pack, at 57%, ahead of Germany (35%) but behind Poland (81%).

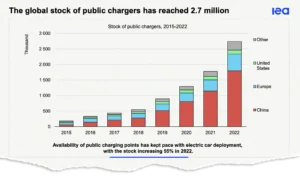

In its 2023 global EV outlook, the IEA notes that most charging is done at home, but that public infrastructure remains important. It says:

“While most of the charging demand is currently met by home-charging, publicly accessible chargers are increasingly needed in order to provide the same level of convenience and accessibility as for refuelling conventional vehicles.”

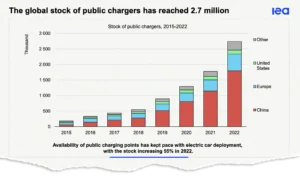

In a launch presentation for the report, the agency says that charging infrastructure “kept pace” with the growth of EVs in 2022, with the stock of charging stations rising by 55%.

There were 2.7m public charging points worldwide at the end of 2022, the IEA says. It adds that 60% of slow charging points were added in 2022 – and almost 90% of fast chargers – were in China.

FALSE: ‘Britain’s creaking power grid cannot cope with charging electric cars’

During the summer of 2023, the Sun newspaper made a series of false arguments against EVs as part of its “give us a brake” campaign “to protect drivers from a rush to net-zero”.

In one August 2023 article, for example, the Sun claimed falsely that “Britain’s creaking power grid cannot cope with charging electric cars”. This is described as a “myth” by National Grid, the company that owns and operates the UK’s electricity network.

A January 2023 comment for the Sun by the climate-sceptic motoring lobbyist Howard Cox also claimed that the UK’s grid would have problems meeting demand for EVs. He wrote:

“Unless the capacity of the national grid is expanded by tens of gigawatts, there will be insufficient power to meet the proposed growth in battery-powered electric vehicle ownership and maintain anything like our current treasured freedom of motoring movement.”

While the specifics have shifted, the spirit of the Sun’s false claims recall a series of 2017 articles – which Carbon Brief factchecked at the time – that incorrectly and implausibly said the UK would need 20 new nuclear plants to meet the demand for electricity from EVs.

(The Sunday Times later removed this wildly overstated figure, issuing a print correction that acknowledged a “significant miscalculation based on a confusion of energy and power”. The false claim remains, more than six years later, in the article’s web address.)

Of course, there is no question that the transition from combustion engine cars to EVs will dramatically reconfigure global energy demand – as well as cutting emissions. It will cut demand for oil, reducing imports and energy security in countries such as the UK and China.

At the same time, EVs will become a significant new source of electricity demand. In its latest report, the IPCC states: “Decarbonising the transport sector will require significant growth in low-carbon electricity to power EVs.”

(The IPCC notes that decarbonising transport with “energy-intensive fuels, such as hydrogen, ammonia and synthetic fuels” would require even larger increases in electricity generation.)

EVs already used an estimated 110 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity in 2022, according to the IEA, equivalent to the entire annual consumption of the Netherlands – or 0.5% of global demand.

This could rise tenfold, to 1,150TWh in 2030, if countries meet their climate pledges, the IEA estimates, equivalent to nearly 4% of global electricity demand. These EVs would cut global oil use by nearly 6m barrels per day, around 6% of current demand.

According to BloombergNEF, EVs will add 12-14% to global electricity demand in 2050.

In the UK, EVs would increase electricity demand by up to 38TWh in 2030 and 88TWh in 2035, according to the latest scenarios from the National Grid Electricity System Operator (ESO). This would cut cars’ demand for petrol and diesel in 2030 to 27-45% below current levels.

In addition to raising annual demand for electricity, there have also been fears that uncontrolled EV charging could increase the peak load on electricity grids.

UK newspapers such as the Daily Telegraph were once again quick to highlight these supposedly insurmountable problems, with a 2017 article saying plans to ban petrol and diesel car sales by 2040 were “unravel[ling] as 10 new power stations needed to cope with electric revolution”.

Once again, however, the company that actually runs the UK’s electricity network sees things differently. National Grid ESO says EVs could, in fact, support the network by storing excess generation from renewable sources and “giv[ing] [it] back to the grid in times of high demand”.

It says the country’s grid could “capably handle” an overnight switch to EVs, thanks to reductions in peak demand over the past two decade:

“Do the electricity grid’s wires have enough capacity for charging EVs? The simple answer is yes. The highest peak electricity demand in the UK in recent years was 62GW [gigawatts] in 2002. Since then, the nation’s peak demand has fallen by roughly 16% due to improvements in energy efficiency. Even if we all switched to EVs overnight, we estimate demand would only increase by around 10%. So we’d still be using less power as a nation than we did in 2002, and this is well within the range the grid can capably handle.”

The firm adds that it is, nevertheless, working with electricity distribution companies, government and others to ensure that “the wires, the connections to charge points” are in place to support EVs.

The IPCC says EVs “provide several opportunities for supporting electricity grids if appropriately integrated”, whereas they could “negatively affect the grid” if there is a lack of integration. It points to the use of “smart-charging” – where EVs are mostly charged during periods of low demand – which it says can cut the impact on peak electricity demand by 60%.

FALSE: ‘How your super heavy EV produces MORE pollution than petrol and diesel cars’

A July 2023 article from the Sun claimed falsely that EVs “actually end up producing MORE pollution than petrol and diesel motors”.

The article’s headline statement is false because it is framed very broadly, implying that EVs produce more “pollution” in general than combustion engine cars.

In fact, although it mistakenly refers to “milligrammes of carbon dioxide per kilometre from [an EV’s] four new tyres”, the article focuses more specifically on fine particulates (PM2.5) from tyre wear.

Even on this narrower point, the article is at best incomplete. Tyre wear is only one source of particulate matter from vehicles, along with exhaust emissions, brake wear and road abrasion.

In contrast to the impression created by the Sun article, the UK government stated unequivocally that the shift to EVs would have the co-benefit of “cleaner air”.

The government document, published in early 2023, contradicts earlier statements from then-UK environment secretary George Eustice. Giving evidence to MPs in 2022, he raised questions over the air quality impact of shifting to EVs, saying:

“The unknown thing at the moment is how far switching from diesel and petrol to electric vehicles will get us. There is scepticism. Some say that just wear and tear on the roads and the fact that these vehicles are heavier means that the gains may be less than some people hope, but it is slightly unknown at the moment.”

The 2023 document notes that EVs have “no exhaust emissions of particulate matter (PM) or NOx [nitrogen oxides, which are emitted by petrol and diesel engines and which contribute to poor air quality”. It puts the net economic benefits of cleaner air from EVs at £1bn in present value terms.

The document refers to a report from the government’s air quality expert group and says that the non-exhaust emissions of EVs compared with conventional cars are assumed to be equal.

The expert group says that EVs “should” have lower brake wear emissions due to using “regenerative braking” rather than brake pads, but adds that tyre and road wear emissions increase with vehicle weight. The “net balance” between these effects “remains unquantified”.

A more recent study puts numbers on these different factors and estimates that EVs would cut emissions of PM by around a quarter in urban environments, with the benefits of regenerative braking outweighing the impact of heavier vehicles on tyre wear.

Another recent study finds that the shift to EVs in California has already led to observable health benefits from cleaner air. The study says:

“This study provides real-world evidence supporting air quality and respiratory health co-benefits from the EV transition, using observational data during a natural experiment of the early phase EV transition in California. We found statistically significant evidence that within-zip code increases in EV adoption were associated with decreases in rates of asthma ED [emergency department] visits.”

The Sun article reports findings from independent testing firm Emissions Analytics that EVs are, on average, heavier than their combustion-engine equivalents, resulting in “20% more pollution”.

Motoring organisation RAC moved to quickly “set the record straight” over Eustice’s remarks, commissioning a brief report from Dr Euan McTurk, a consultant battery electrochemist.

McTurk also notes reduced brake wear in EVs, pointing to the experience of a taxi firm in Dundee, among others. Summarising McTurk’s conclusions on tyre wear, the RAC states: “[EV] tyre wear is similar for the non-driven wheels and only slightly worse for driven wheels.”

While the Sun article presented a false and misleading picture of the pollution impacts of EVs, it is the case that they currently tend to be heavier than equivalent combustion-engine cars.

Along with the much broader shift in consumer preferences towards larger, heavier SUVs, this does present problems for transport infrastructure.

An August 2023 article in the Guardian reported on SUVs being too large to fit in car parking spaces, a phenomenon it referred to as “autobesity”:

“More than 150 car models are now too big to fit in average car parking spaces, according to analysis conducted by Which?. While the size of the standard parking bay has remained static for decades, cars have been growing longer and wider in a phenomenon known as ‘autobesity’…All three of the widest cars are sports utility vehicles (SUVs).”

Other newspapers have chosen to focus their reporting on EVs, with an April 2023 article in the Daily Telegraph saying: “Car parks could collapse under the weight of electric cars.” Another Daily Telegraph article was titled: “Sheer weight of electric vehicles could sink our bridges.”

In June 2023, US factchecking site Politifact faulted claims by Republican presidential hopeful Nikki Haley, who had said: “Electric vehicles are so heavy that our roads and bridges aren’t capable of handling that.” The site concluded:

“Electric vehicles generally weigh more than gasoline-powered cars…But infrastructure experts said that by far, more damage to roads and bridges is caused by weightier vehicles such as semitrucks [articulated lorries].”

Similarly, the claim in a frontpage Daily Telegraph story that EVs cause “double” the pothole damage of petrol cars, was branded “rubbish” by TU Eindhoven’s Auke Hoekstra.

Hoekstra also points to the “disproportionate impact” of the heaviest vehicles, such as trucks and vans. He goes on to argue that batteries are getting twice as light per unit of capacity per decade, meaning that: “By the time most vehicles sold will be EVs…they will NOT be heavier.”

(The Daily Telegraph article cites “analysis led by the University of Leeds”, however, the university’s press office notes that its research does not say anything about potholes.)