Nonette Royo: Indigenous knowledge can help us survive and overcome the climate crisis

Indigenous Peoples and local communities live on and manage more than half of the world’s land, yet they only have legal ownership of 10% of these territories. Robust Indigenous and local land rights are vital for managing forests, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, preserving biodiversity, and improving livelihoods.

Nonette Royo, Executive Director, Tenure Facility, has spent more than 30 years fighting for the tenure rights of Indigenous Peoples in the world’s tropical forests, in regions ranging from Latin America, to Southeast Asia and Africa. As Executive Director of Tenure Facility, Nonette has helped to map, and protect some 18 million hectares of land – an area equivalent to the size of Cambodia – which is expected to double this year. We spoke to Nonette about how a clear commitment to inclusion underpins her work to strengthen the tenure of Indigenous Peoples and boost their ability to preserve and protect traditional lands and resources.

How does Tenure Facility support Indigenous Communities to protect nature?

Tenure Facility offers grants and technical assistance directly to Indigenous Peoples and local communities, who are self-determined and work collectively, in their efforts to secure tenure, with a particular focus on mitigating climate change, reducing conflict and promoting gender equality.

Behind the scenes of our richest natural ecosystems, from the tropical forests of Peru, to Guyana and Indonesia, Indigenous Peoples act as guardians, helping these natural realms to survive and thrive. To boost their ability to tend, nurture and protect their territories, Tenure Facility shortcuts the process of getting funds to Indigenous Peoples.

Members of the Indigenous Siekopai community who reside in the Amazon jungle along Ecuador’s border with Peru. Credit: Andrés Yépez/Tenure Facility.

Traditionally, funding for Indigenous Peoples has been beset by bureaucracy, such as onerous testing of their abilities to manage financial resources. This is a major challenge. For example, a recent report showed that 0.13% of climate funding has actually been reaching Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities for tenure and forest management. We’ve proved over the last five years that large amounts of funding – of around one million US dollars per year – can be successfully channelled into Indigenous Peoples who are best placed to drive impactful, accountable nature protection.

Our mission is to strengthen the capacity of Indigenous Communities to protect the forests where they live – and upon which we all depend for biodiversity and as carbon sinks. We conducted deep consultations with Indigenous Peoples on how to achieve our mission – and found that strengthening land rights was critical to boosting their ability to preserve, protect and enjoy their traditional lands. We also support knowledge-sharing across local communities, enabling conservation tools and insights to be shared within Indigenous networks that share the same languages, but which can span different countries.

How does securing Indigenous land rights translate into nature protection?

Once, when Indigenous Peoples were isolated in their territories no one challenged them. But over time, external parties increasingly entered their territories to steal resources, such as timber and precious metals. Indigenous Peoples’ land rights were questioned, often violently, with miners and loggers often forcing communities out of their ancestral lands.

To stop this, it’s vital for Indigenous Peoples to secure legal tenure of their land. They need our help to come to the table, to show the world their ability to protect land, for their own livelihoods – and for the greater good. Primary forests sustain communities and economies at large, from contributing to healthy soils for agriculture, to storing vast amounts of carbon, to storing freshwater in aquifers. Research over the last five years also shows that deforestation rates are three to four times lower in territories with secure tenure – ownership is key to conserving what we have and restoring what we’ve lost.

A group of women involved in the management of a local community forest concession and reforestation efforts in the southwest of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ley Uwera/Tenure Facility.

How did you become a champion for Indigenous Peoples?

I was raised in the forests of the Philippines where Indigenous Peoples were very prominent. It was clear very early on in my life that territories were being violently stolen. People were dying defending their homelands. I had a strong desire to help – but frankly I was also afraid to die in the process. I was faced with the question, “Is the only way to protect my ancestral lands to take up arms, or is there a better way?”

This question led me to explore how the law could be used as a tool to turn land tenure from a violent fight, into a negotiation. After decades of conflict, I wanted to stop the violence from affecting my own friends and family even further, as well as people facing similar troubles in other countries. So, I studied the legal routes to solving land rights issues peacefully.

National constitutions usually assure that everyone in a country has the right to be recognized and respected, which provides a starting point for the case to implement tenure rights within existing laws and policy. In further study of historical documents I realised that there is a corpus of documents supporting collective rights for the use and ownership of land. For example, in the late 19th century when the Philippines was governed by the United States. I found that the governance of Indigenous territories was affirmed by the US Supreme Court, ascribing land right rights to the community.

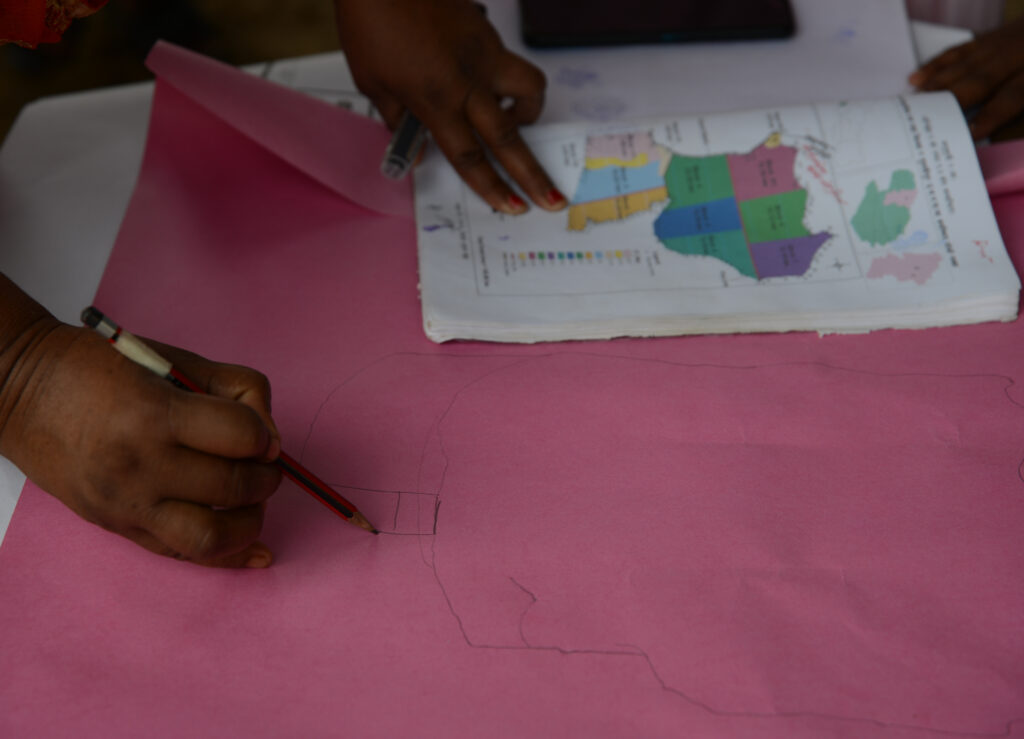

For cases to stand up in the courts we had to establish legal standing, so we measured and mapped the boundaries of key territories to establish ‘titles’ for land. This gave indigenous Peoples a seat at the table – from which they could express their abilities to manage the land sustainably – providing long term benefit to the country and to their own communities, as opposed to razing and extracting from the land just for short-term gain.

At this time, around 30 years ago, the Philippines faced huge deforestation; so it was imperative that the law began to be applied to protect it. Over time, however, nation states began to make global commitments to protect the climate and biodiversity in the international arena. Subsequently, these targets began to be translated into laws and policies which would unlock the vast potential to boost Indigenous Peoples’ abilities as key partners for delivering on nature and biodiversity commitments. From these origins in the Philippines we progressively scaled Tenure Facility’s model, in regions such as Indonesia, and onwards to Latin America and Africa.

How can Indigenous knowledge help us to solve the climate crisis?

From the perspective of Indigenous Peoples, the climate crisis is not just a heating crisis – it’s a crisis of lifestyle. Humankind’s relationship with nature is in crisis due to a loss of respect for, and connection to nature. The longevity of Indigenous Peoples stretches back thousands of years as they live by the central principle of “only take what you need, and leave the rest for future generations.”

Members of the Gond tribe, breaking and flaking seeds to extract oil in a forest village in east-central India. Credit: Rohit Jain/Tenure Facility.

Indigenous knowledge can help us to return to the wisdom of our ancestors to survive and overcome the climate crisis. Everyone – whether white, black or whatever colour – has the inherent ability to coexist with nature. But somehow we have put ourselves in a place that is so safe and sanitised – with everything bought from stores – that we have created the illusion of separation from nature. In reality, everything that we consume and use is from the natural world, and our disconnection from our source places puts humankind into existential danger.

When we visit our partners, whether in the Amazon, or the forests of Guyana, we witness the palpable, lived experience of Indigenous Peoples as part of the natural ecosystem. Soil and land use are fundamental to everything, including water. As well as balancing the climate, forests and land ensure the balance of our water cycle, holding moisture, and storing and transmitting freshwater through aquifers to rivers and seas. Respect for the conditions which support life is central to Indigenous knowledge.

The existence of Indigenous Peoples is inextricably linked to nature itself – if nature fails, their communities fail, and vice versa. We can relearn the value of this connection from Indigenous Peoples – it’s not just about science, it’s about being part of nature, to protect the conditions for our mutual survival.

Nonette Royo

These are not just ordinary communities. These are Peoples who have lived over long periods of time through knowing the territory, tending to the forest and adapting their livelihoods around nature. There is meaning to the ways that the seasons shift, in how nature expresses herself, if we know how to listen. As the climate has changed Indigenous Peoples have adjusted their ways – especially their use of the land – to reflect the changes in the seasons. As well as being indispensable to our mission to tackle the climate crisis, Indigenous knowledge can also contribute to better decision-making when it comes to climate adaptation.

How do the customs of Indigenous Peoples support their protection of nature?

As an example, in Indonesia we have partners that are both Indigenous People and local community organizations. These groups are self-determined, with a long, long history of autonomously managing the land.

Strikingly, for Indigenous communities to map a large territory of forest, say four million hectares, is not a technical task. It’s actually a social process of remembering what the land was – and how it was managed by different tribes. Totems play a significant role as symbolic records of rituals and ancestral connections between different tribes, which show how they worked together with the natural features, such as the mountains, rocks and sea.

I witnessed the mapping of one area, which began with a re-telling of a story of a cycle that cannot be broken. Within the stories were taboos, such as restricting too many trees being taken from one area, and preventing the removal of certain trees, in certain places. This wisdom of how to protect nature and land is ingrained over generations, it’s constantly passed from elders to youth. Due to the recirculation of knowledge over time the biodiversity within Indigenous Peoples’ territories thrives.

Why is direct funding of Indigenous Peoples essential?

Direct funding of Indigenous Peoples is essential, firstly as it acknowledges that communities that have lived within forests for many generations are acutely aware of the challenges they face and are best placed to implement solutions. Living in partnership with nature can be precarious, but over time, communities have learned to survive and thrive by supporting nature. Few external parties have that lived experience, so it makes the most sense for Indigenous Peoples to lead on projects and to allocate funds.

Mapping efforts are integral to recognising and securing land rights as well as ensuring community participation. Credit: Keshab Raj Thoker/Tenure Facility.

Now externally-driven problems, such as climate change and deforestation threaten the natural ecosystems that communities depend on, causing issues such as food insecurity, wildfires and droughts. Indigenous Peoples need funds to protect themselves and their territories, but traditionally, only a tiny amount of climate and development funding trickles down to them. This is due to an entrenched mistrust of Indigenous Peoples and misplaced doubts in their ability to handle money. Our experience and data completely debunks these myths. Indigenous Peoples can indeed allocate funds, and conduct effective reporting, for example, using technologies, such as smartphones for data collection and reporting, or aerial drones for surveying lands or GPS devices for mapping.

From providing direct finance to local communities, we’re seeing that the metrics of accountability, effectiveness and efficiency are all met. Now is the time to break down those bureaucratic barriers to fully empower Indigenous Peoples to lead.

What does inclusion look like for Tenure Facility?

In the context of Tenure Facility’s work to expand the sustainable management and protection of their forests and lands, real ‘inclusion’ means providing open access to all information at the right time, which promotes full understanding and engagement.

To promote their self governance it’s important to ensure that the leaders of Indigenous Peoples are represented fully, plus an understanding of the processes which underpin the election of those leaders is also key. Tribal leaders have a vision for how the community exists with nature which lives in their processes and protocols that are passed down, reinforcing their cultural identity and social cohesion within the community.

For example, in Indonesia the community regularly gathers in traditional longhouses to mark the seasons, and conduct cultural ceremonies. Longhouses are central hubs for the community, providing a space for storytelling and sharing of customs and traditions. To build trust, it’s important that the process of inclusion is understood in the context of these gatherings, to understand the key actors, the areas that they have control over and the rites of passage. This is critical to understand Indigenous youth – trust needs to be built with the young people that are next in line as leaders – and by understanding the protocols of the community, their governance and sovereignty can be understood.

An appreciation of their practices is key – not just internally within the group, but also their role within networks of neighbouring tribes which monitor and protect territories. One cannot overlook how tribes work together, as decisions are also made between governance units within neighbouring territories. Overall, it’s vital that these processes and protocols are respectfully followed – once that is clear, then Indigenous Peoples are keenly interested in developing partnerships with people coming from outside.

Real inclusion means actually learning about these inter-group relationships. The key words here are self-determination and trust. You can’t just expect to come into the group and expect to be a decision-maker by virtue of being a donor. We’re very careful about that.

We operate using the right to ‘Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)’, which is recognised in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP); aligning with the universal right to self-determination. FPIC is a clearly defined principle ensuring that no stakeholders are excluded from discussions about the protection, governance, planning and sustainable use of Indigenous forests and lands. It cannot just be a top-down proposal, which is presented with the expectation of an agreement and a pot of funding.

This means providing groups with the right information, at the right time, to the right set of community stakeholders through a facilitated, informed conversation. This approach helps to build consensus, on the basis of the full understanding of all of the available information. FPIC is a living principle, taking account of the many groups of Indigenous Peoples, the many interests and many ways that they make decisions about the land.

Beyond funding, how else can Indigenous Peoples be supported?

Besides funding to scale up land and forest tenure reform policies and legislation, what’s important is to make Indigenous Peoples visible. Indigenous Peoples don’t show up in typical clubs, societies and associations, so it’s vital that their interests are observed in policy and legal frameworks. The strength of a nation is the diversity of its people – it’s fundamental that this is recognised within policy and law. You can see the benefits, for example, in Brazil and Columbia, where recent government partnership with Indigenous Peoples is beginning to have a real impact on reducing deforestation, and not a moment too soon.

How effectively are governments grasping the need for land rights for Indigenous Peoples?

There is progress – in some countries it’s fast, and in others it’s slow. The advantage now compared to 30 years ago when I started is that the climate and biodiversity challenge is now prominent in the international arena. Governments are now bound by agreements which in turn, leads to the introduction of policies and standards.

Negotiators make commitments when they come to COP, or other UN negotiations, then the realisation that action depends not only on policy, but the implementation budget and conservation expertise of countries. With the legal and policy context set, the challenge now is to show governments the potential for Indigenous Communities to help deliver on their commitments. This is where the rubber hits the road.

Progress is slow in places where governments are less familiar with nature protection and restoration. In those areas, we offer governments exposure to our partners, and the opportunity to make powerful Indigenous allies. Governments love working with our partners, due to the vast knowledge that they hold.

For example, in the upper reaches of the Colombian forests, our core partners are now negotiating with the Colombian government to elevate the role of Indigenous shamans in conserving what we have and restoring what’s been lost. This would be a very unique relationship, where a spiritual group consults a legal and political group, to solve common challenges. It represents a major step forward.

What gives you hope?

I feel inspired that we have reached a point of urgency that most people now understand. The scaffolding of environmental commitments has been constructed, from the 30x30x30 goals on nature & biodiversity, to net zero. Now we must focus on designing the processes to meet those targets. Only once one has begun to dream of an ideal situation, can one then actually figure out the way to reach it. We’re shaping the dream of a planet where we regain our respectful, mutually restorative relationship with nature. Once we have agreed that this is where we want to go, it is within our ability to make the journey there.

Watch the full interview below.

Nonette Royo has spent more than 30 years fighting for the tenure rights of indigenous communities in the world’s tropical forests. As executive director of Tenure Facility since its founding in 2017, she has worked alongside Indigenous Peoples and local communities to strengthen their tenure and ability to preserve and protect traditional lands and resources.

During this time, she has overseen the organisation’s dramatic growth to one of the world’s leading financing mechanisms offering longer-term, flexible, timely, and direct support to community organisations across 20 countries.