“Celebrating resilience is glossing over the deep harm and repetitive trauma these communities are experiencing”

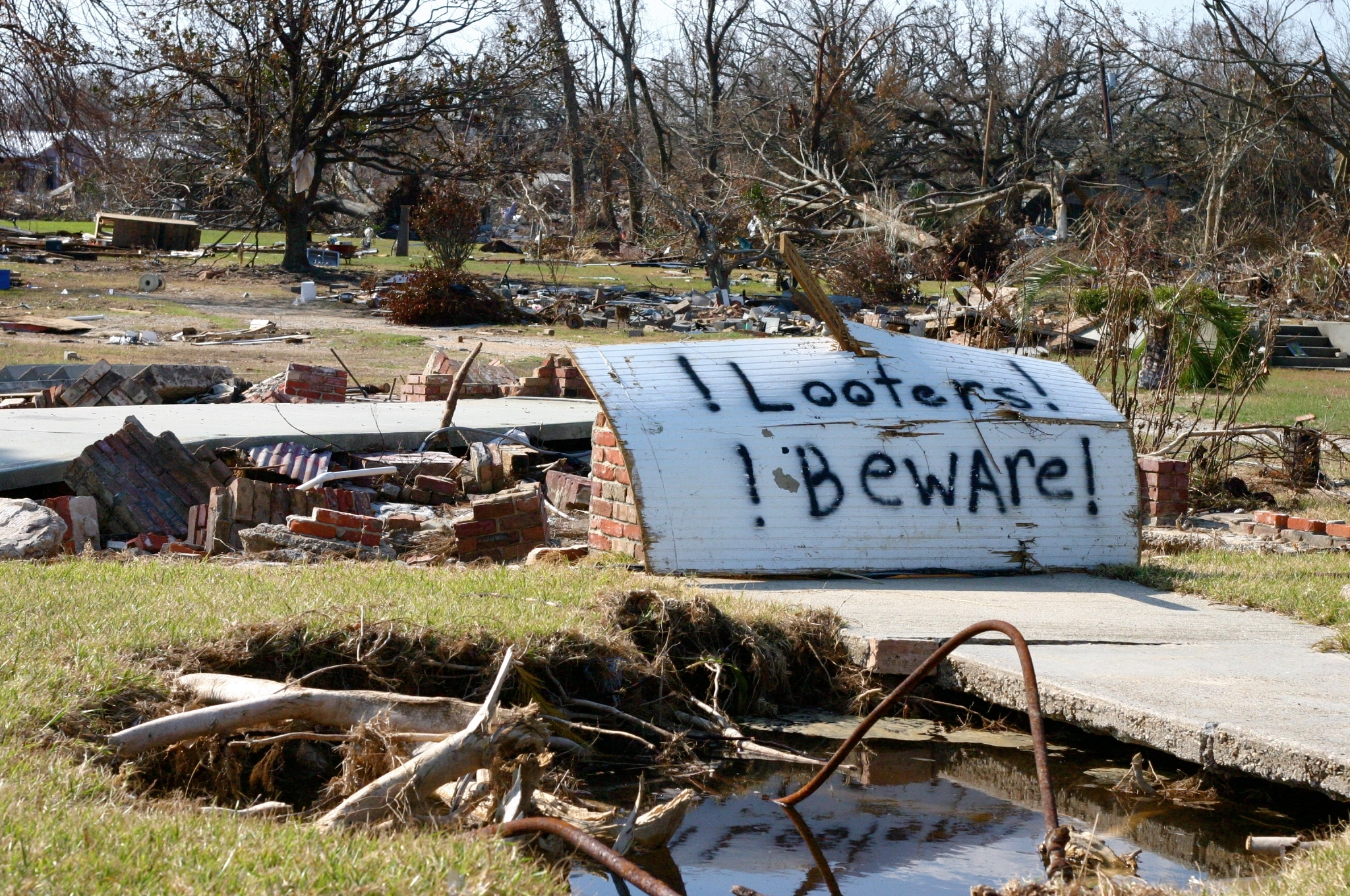

16 years to the day that Katrina tore through Louisiana, Hurricane Ida reversed the flow of the Mississippi River and blew thousands of roofs off buildings. Ida’s 150 mph winds in August 2021 tied it for the fifth-strongest hurricane to ever hit the mainland US and left more than a million households without power.

For Louisiana’s residents, such events are now part of their existence; life has become an endless cycle of climate disaster and recovery that compounds the state’s chronic poverty and deepens the widening gulf between rich and poor. After Mississippi, Louisiana has the second highest rate of poverty and child poverty in the US.

In 2016, 54 out of 64 Louisiana parishes were declared a national disaster due to a combination of weather events, from tornadoes to the Great Flood of 2016, which flooded over 145,000 homes and cost an estimated $15 billion.

The road ahead will not be easy, but for Camille Manning Broome – President and CEO of the Center for Planning Excellence (CPEX) – an organization that delivers visionary planning processes to communities across Louisiana – a happy ending is possible.

It’s an outcome, she says, the state can only accomplish if the collective reigns over the individual, near term thinking gives way to long term planning, and equity drives the race.

Charlotte Owen-Burge: What is the current situation in Louisiana?

Camille Manning-Broome: Climate change is unavoidable here. We are on the frontlines, experiencing an amalgamation of threats, from relative sea level rise; heavier rain events coupled with longer periods of drought; more intense and longer, lingering hurricanes; and extreme heat coupled with high humidity.

In the past decade alone, our state has had annual disasters that have put us in a constant state of disaster response. We never fully recover.

Climate vulnerability is compounded by economic vulnerability. Every economic shift and climate disaster reveals long-standing disparities along the lines of race, income and health, with poor and marginalized communities bearing the brunt of these shifts.

Our vulnerabilities make it hard to get ahead of these compounding disasters. Hurricane Katrina brought a tremendous amount of money to New Orleans for flood protection, and that investment paid off during Hurricane Ida. But the reality is that Katrina was not a once-in-a-lifetime event and New Orleans is just one of the many highly vulnerable places that need protections in place. It still has not rebound its population.

The Great Flood of 2016 flooded over 145,000 homes and cost an estimated $15 billion.

Every hurricane season has the potential to be more active than the one before. We see communities like Lake Charles still struggling to recover a year after a string of disasters in 2020 — two hurricanes, major flooding and a devastating winter storm. This doesn’t bode well for the communities that were also just recently hit by Hurricane Ida. More than six weeks have passed and many people are still living in tents; there are some communities that haven’t had power restored.

But we also have to choose to see the new opportunities in front of us. We can choose to be a leader in a just energy transition, putting our industrial expertise to work in the electrification and the renewable space while opening up new economic opportunities for people who have long been marginalized. We can be an example to the rest of the world in climate adaptation and mitigation.

We’re at Ground Zero, building the boat in the water and there’s no time to waste. We have to do it now.

What will it take to equip Louisiana with the resilience that it needs?

Building resilience in Louisiana is more than just hardening our infrastructure, reducing emissions or even taking other climate focused measures. It requires the strengthening of the underlying systems of infrastructure, governance, economy and social networks that largely determine how a city, town, region or state functions both on a daily basis and during times of disaster. It’s not a one size fits all approach.

What constitutes resilience varies from one community to another, and every place is unique. Nowhere is that more true than Louisiana. Building resilience means strengthening the very systems that drive our economy, environment, risk profile and social and political structures in ways that empower communities.

Louisiana is in a constant state of disaster and recovery mode — which exacerbates already deeply entrenched social and economic tensions.

It means addressing the root causes of poverty, economic exclusion and racial divisions. In Louisiana, it also requires sensitivity to the very unique risk profiles and political and cultural factors. We have a large Native American population, and those tribes and communities trickle across our most vulnerable coasts and coastline and they are struggling.

Perhaps the most important change that must take place for Louisiana to achieve resilience is a shift in values that elevates the collective over the individual, and future sustainability over near-term gains.

People are tired of having to always be resilient. We can’t keep asking individuals to be resilient on their own. We need leadership at all levels, committed to developing systems and structures that support the adaptation and mitigation needed to advance resilience for all of our people.

What do you identify as the biggest challenges? And how do you think they are overcome?

Adaptation is what’s critical to our long-term resilience, but it’s especially challenging when we’re caught in a continuous cycle of disaster and recovery that’s only gaining speed.

In the wake of each disaster, elected officials and residents are faced with catastrophic losses. They’ve lost everything, and they want to expedite recovery and return to normal as soon as possible. But the “normal” of yesterday no longer exists — we have to find ways to recover and adapt simultaneously in order to use the resources that are available efficiently and to reduce the future impacts of our people.This requires facing very uncomfortable and unpopular realities about what our future looks like.

We’ve got to be honest and transparent about the science and the projections of risk. We have to insist on informed decision making at all scales. And we have to be willing to do things differently. This involves everything from the way we use our land and develop our communities, to the way in which we engage people in our economy.

Another issue of importance is climate driven migration. In the absence of predictable resources or policies to support resettlement, we see that people with the means to do so voluntarily move to safer places when they determine that the risk outweighs the benefits. On the other hand, people with low income or other vulnerabilities are not able to move even if it costs them more to stay. They’re left behind, facing increasingly dire circumstances as tax bases and essential services decline and negative climate impacts increase. When those networks start to break up, it’s a domino effect of bad outcomes from an individual to a systemic level.

We are witnessing first-hand that adaptation is means based. This is just one example of why equity must be at the forefront of approaches to both adaptation and mitigation.

We celebrate our frontline communities for being so resilient. It’s what’s said across the news networks by everyone: “Louisiana is resilient”. And our people are so resilient, but we’re past the point where celebrating resilience is glossing over the deep harm and repetitive trauma these communities are experiencing. We have to do much better by engaging the frontline communities and leading with equity in all our practices and policies, in the way that we allocate resources, and how we design programmes and economic development strategies to achieve a just transition.

For Louisiana to achieve resilience, we must take an authentically holistic approach. This requires a whole-of-government strategy that has agencies at the state and federal levels, horizontally aligned in the efforts to support climate adaptation and mitigation, as well as vertical alignment at the federal, state and local levels.

Achieving resilience is going to require great things from us, but I believe that we can do this as I have seen Louisiana’s ability to change and innovate. I’ve seen the heart that Louisiana people have to fight for their home, their culture, and their families.

What will lack of planning lead to?

Katrina was a tipping point for us. It was the time when a lot of societal values shifted, and everyone responded, including the government and groups across the state. We’ve since done a lot of planning. We have our coastal master plan which projects the risk and landscape changes to 2050 and identifies projects and large-scale investments that must happen to protect our people and natural assets.

Other planning and adaptive measures that we’ve led the way on include the community driven planned resettlement of the Isle de Jean Charles band of biloxi-chitimacha-choctaw, making the tribe the country’s first official climate refugees.

This planned resettlement will likely not be the last. The state’s climate forecast predicts that sea level will rise between 1.41 and 2.7 by 2067, which would place around 2.3 million people currently living in Louisiana’s coastal area at high risk of flooding.

Perhaps our biggest gap in planning is on the question of climate-driven human migration. There is currently no vision in place for what that migration should look like. This problem of how we resettle entire communities of people in an equitable way is too big for local governments to figure out on their own. From a planning perspective, we also have to think about how to equip the receiving communities. We should already be planning those communities for people to move to. People will move if they see opportunity, and planning can guide this. They need to have better options. Those communities need support to build the infrastructure that will have to serve that incoming population, some of which will be high-needs because of the traumas and hardships they have endured.

It is no coincidence that after every major disaster, rates of suicide, anxiety, depression and babies born with opiates in their systems, spike. It’s a failure of human rights to ignore these implications.

The next 10 years are critical. So much of keeping temperatures below 1.5C will depend on the path we pursue as a global collective. Here in Louisiana, 66% of our emissions currently come from oil, gas, and the petrochemical sectors. A combination of incentives, regulations, financing and technological advancements will have to be deployed rapidly. We’ll have to electrify our industrial sector and build out the wind and solar power to eventually replace fossil fuels.

66% of Louisiana’s emissions currently come from fossil fuels. But change is on the horizon, as the state embarks on its Race to Zero emissions.

What does the future of Louisiana look like?

In a way, Louisiana is the testing ground for all the complexities of climate change adaptation and mitigation. My hope is that the rest of the world will see what we accomplish here and we can export that knowledge for other states and nations before they too reach the frontlines. My vision is that Louisiana can develop and present best practices across the globe.

Human migration due to climate change will continue to be a major issue worldwide. And by 2030, I hope that we’re able to explore equitable models for buyouts, relocations and resettlements for the most at-risk communities.

I’m also really looking forward to the future because I believe that we can demonstrate the creation of an entirely new innovation ecosystem for our economy as we move from a high to low carbon.

But most importantly, accomplishing all of this will have the result of removing an enormous burden from our poorest residents. We have the opportunity – right now – to significantly decrease poverty and make life better for millions of Louisiana families, while also securing our climate future. We have to choose a Liveable Future.

The opportunities for adapting, while shifting our economy to be prosperous, sustainable and equitable, are plenty — we just have to have the will and the courage to seize these opportunities. We must prioritise our collective interest and push towards that shared future. And I believe that we can do it. I already see it happening.

To find out more about CEPEX’s work, please click here.

To find out about Louisiana’s Race to Zero emissions, please click here.