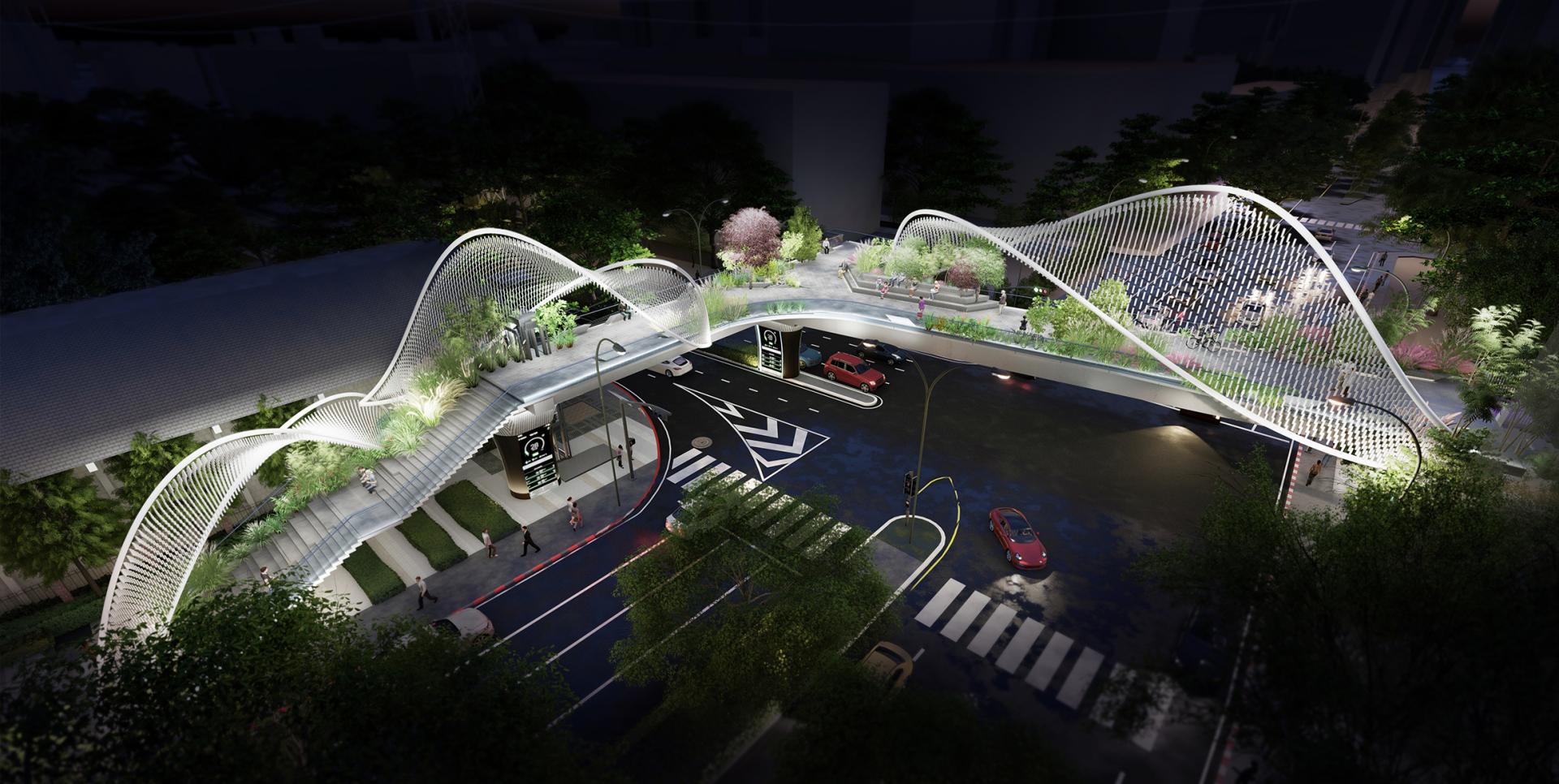

A proposed design for a pedestrian overpass in the centre of Bangkok; Main image: The Chao Phraya Sky Park

Bangkok is one of the world’s great cities, a place that – in pre-COVID times – attracted more than 20 million tourists annually. Add a local population of 10 million, and it is no surprise that the city is one of the most congested in the world. It also has one of the lowest amounts of public green space per capita in Asia, at under 7sqm per resident, compared to an average of 39sqm per resident across 22 major Asian cities.

Enter Bangkok250, a project that aims to make Bangkok’s inner city more ‘liveable’ by 2032, which just happens to be Bangkok’s 250th birthday. At the forefront of this drive is the Urban Design and Development Center (UddC), an organization set up to promote public health through a better city environment, and takes part in multiple urban regeneration projects across Thailand.

One of the most striking projects the UddC has led is Chaopraya Sky Park, billed as Thailand’s first ‘garden bridge’ when it was opened last year on an unused rail bridge. “It was one of the most important projects helping to regenerate Bangkok’s inner city,” says Dr Niramon Serisakul, UddC’s Director.

“Bangkok is overcrowded, but there are plenty of underutilized spaces,” says Dr Niramon. “The Sky Park was just a rail structure that was left untouched for 20 years.” Bangkok is not the first city to understand the environmental and economic benefits of ‘greening’; New York’s High Line for example, an elevated park on former railway tracks, has breathed new life into the city’s lower West Side, and has had a multitude of environmental and economic benefits.

Alongside the Bangkok250 project is the Green Bangkok 2030 project, which was launched at the end of 2019, as part of Thailand’s goal to reduce greenhouse gases by 20-30 per cent by 2030. The main aim of the project is to increase the number of sustainable, quality green spaces across Bangkok. The project has three main targets: increase the ratio of green space in the city to 10sqm per person; have trees covering 30 per cent of a city’s total area, and ensure footpaths meet international standards

Progress is being made, with 11 new parks set to open in the first phase of the project, followed by a 15km greenway, as well as plans to improve the city’s footpaths. Other projects include the Thammasat University Rooftop Farm, which integrates flood control, water and energy conservation and solar power, so students can grow organic food on the university’s roof. Another is The Big Trees project, which trains tree surgeons and campaigns against mass tree felling and overharsh pruning of trees across the city.

None of this is easy, given the many stakeholders that are involved in managing Bangkok’s urban environment. “Even though the then governor wanted the Chaopraya Sky Park, and there was lots of support, we had more than 40 consultations with different agencies and it took more than five years to finish,” Dr Niramon says.

“UddC is an urban agency that tries to introduce a new methodology in urban planning,” Dr Niramon says, “so we try to engage all stakeholders and potential partners in discussions and decision making as well as the local community and local government. Urban planning is a complex process, so we don’t just have urban designers, but social scientists, political scientists, geographers and communication experts.”

That complexity is reflected in the challenges of improving the city’s footpaths. “I think the biggest challenge is now the Sidewalk Project, which is a big test to see if everyone can work together. There are lots of telephone lines above the sidewalks, and 18 different agencies take care of these lines; on the sidewalk you have police booths and telephone booths, while under the sidewalk you have many pipes and wires.”

“The international standard for a public sidewalk is a minimum width of 1.5 metres, so two people can walk by as well as a wheelchair user. We try to rearrange the location of the trees and the utilities to the outside to curb, so there is enough room. We designed new ramps so older people and those with limited mobility can access the sidewalks easier,” she adds.

The impetus to improve the urban environment has been heightened due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seen most of us confined to small areas near our homes. “People now do see the importance of having green spaces in the city, and while the quantity is important, but so is the quality,” Dr Niramon says.

“Before when people were bored they could go to a department store,” she says. “But now the city is just reduced to your home, and you realize your home is not pleasant; that you have a really small apartment and you can’t go anywhere, and as you have to walk to the local shops, you see the state of the sidewalks. Now people are thinking that to have a good city or a good home is not enough, that you need a neighbourhood, and you need local parks where you can get out and breathe and meet other people.

And as more projects get complete, more local residents see what’s possible, leading to more demands for a better urban environment. “I think attitudes are changing,” Dr Niramon says, “but it hasn’t reached a majority yet. On a day-tohttps://unfccc.int/blog/the-greening-of-bangkok-day basis, Thais just want to survive, and maybe for many, thinking about ecology is seen as a luxury.”

This article was first published by the UNFCCC

من ضمن الالتزامات العديدة الرائدة التي تم الاستماع إليها في قمة المناخ COP26 إلى نتائج الجزء الأول من اتفاقية التنوع البيولوجي COP15 في أكتوبر الماضي ، هناك اعتراف متزايد بأن معظم التحديات العالمية التي تؤثر علينا، مثل المناخ المتشابك وحالات الطوارئ الطبيعية، يمكن معالجتها من خلال روابطها الحضرية.

The second wave of the Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund, arriving in August, is a prime opportunity for councils and housing providers to upgrade their properties by turning to proven and practical retrofit solutions, says Cara Jenkinson, Cities Manager, Ashden.

In an increasingly challenging and volatile world, the urgent need to decarbonize real estate remains a constant, explains Christian Ulbrich, Global Chief Executive Officer; President, JLL

Karim Elgendy, Chatham House & Martina Juvara, International Society of City and Regional Planners, explain why the UK’s planning system tool could be central to integrating climate change mitigation and adaptation in cities.